I had to abandon a game last season because of threats made by a spectator. This wasn’t a snap decision for me – I am a police officer and deal with abuse on a daily basis. The difference here was that I referee to enjoy football, and no one has the right to put my safety at risk when I expect to go home to my children. Players, coaches and spectators appear to believe it is a right to abuse the referee. (Grassroots referee, England)

The Uefa European Football Championship – commonly known as the Euros – is one of the world’s most valuable sporting events. This summer’s 17th staging, which kicks off in Germany on June 14, is expected to generate commercial revenues of at least €2.4 billion euros (£2bn). Upwards of 5 billion TV viewers will watch the 51 matches, culminating in the final in Berlin’s Olympiastadion on 14 July.

At the heart of this global spectacle are the 19 men whose job it is to keep order on the pitch. Their split-second decisions can decide the outcome of games – and infuriate legions of fans. They are regarded as the best referees in European football (plus one from Argentina) – but, like officials at all levels of the game, have endured abuse from players, coaches and spectators on their journey to the pinnacle of the sport.

One of the two English referees at this year’s Euros, Michael Oliver, was subjected to particularly shocking abuse, including death threats, after awarding a last-minute penalty in a Champions League quarter-final in April 2018. And it wasn’t only him: Oliver’s wife Lucy, also a referee, was sent abusive text messages after her mobile phone number was posted on social media.

Referees of past Euros have had to put up with similar treatment. After the Swiss referee Urs Meier disallowed a goal for England against Portugal in the 2004 quarter-final, he was given police protection and advised to go into hiding after receiving more than 16,000 emails from angry English fans. Stoking the abuse, the Sun newspaper printed his email address and laid out a giant England flag outside Meier’s office in Switzerland.

Dusan Vranic/AP/Alamy

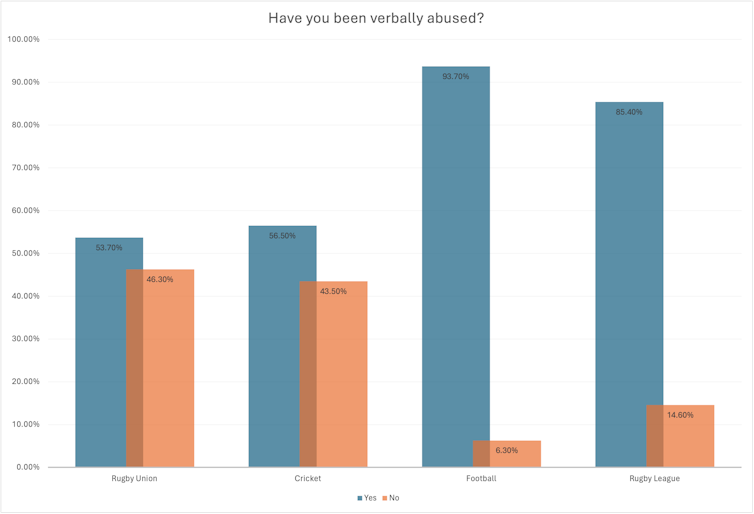

Our recent survey of nearly 1,300 football referees across Europe, Oceania and North America suggests abuse of officials is now endemic at all levels of the game. In another study, more than 93% of football referees told us they had been verbally abused, while almost one in five reported physical abuse. Around half the referees we have contacted say they are considering quitting the game.

As a result, football is lurching towards a crisis as it struggles to recruit and, in particular, retain referees at grassroots levels. While the game is booming across Europe, with girls’ and women’s leagues growing especially rapidly, it’s estimated that one in seven match officials quit every year, with the abuse they face a major cause. Uefa’s head of referees, Roberto Rosetti, calls it “a vocational crisis” that is also putting increased pressure on efforts to bring referees through to elite levels of the sport.

In August 2023, Uefa launched its first ever recruitment campaign for referees – featuring Oliver in the promotional material. Uefa says it aims to enlist around 40,000 new referees each season throughout Europe.

But unless there is a dramatic shift in the behaviour of players, coaches and spectators, Europe’s grassroot leagues will struggle to retain many of these recruits. While money continues to flood into elite football, volunteer referees of all ages will continue to turn their backs on “the beautiful game” for fear of the abuse they may face when they step on to a pitch.

‘The referee pool is almost dry’

In England, aggressive behaviour towards referees has become such a concern that in February 2023 the Football Association (FA) became the first governing body to trial the use of body cameras to reduce abuse towards referees at grassroots levels.

Notices hang on the walls of dressing rooms and the fences of grounds asking players, officials and spectators to show more respect during games. Yet according to another referee we interviewed, these signs are “merely displayed as lip service”:

I’d say county-level, Saturday football is probably the worst example of players using every conceivable way to win, whatever it takes. Abuse, cheap comments towards officials, and a general want to shout foul for almost every contact … Red and yellow cards have not thwarted the wall of abuse and unsporting action that is seen week in, week out.

From 2016, 10,000 referees left English football in five seasons, with the COVID pandemic adding to the difficulty of recruiting replacements – leaving a major shortfall up and down the country.

Bans of up to eight years have been imposed in recent seasons for the physical abuse of male and female referees, who have been kicked, headbutted, punched and spat on. In one local cup final, the BBC reported that the referee had been knocked to the ground and punched by “up to 20 people”.

Even child referees making their first steps in the game are not immune from this treatment. In November 2021, all 13 and 14-year-old referees in Northumberland went on strike one weekend in protest at the levels of abuse they were receiving from parents and coaches. Martin Cassidy, chief-executive of the charity Ref Support, has warned that young officials are being turned off the game by the abuse they see and experience, to the extent that “the pool of new referees coming into the game is almost dry”.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

Such abuse is not a new phenomenon. The abuse of referees dates back before the formation of the English FA in 1863, when gamblers verbally and sometimes physically assaulted referees after blaming them for making decisions that affected the bets they had placed. But there are particular reasons for today’s worsening levels of abuse.

We have been researching referee abuse in football and other sports around the world for the past two decades, and in 2020 published a ten-point plan for how to tackle this abuse. One of the problems frequently highlighted is that referees are seen as “outsiders” who players and spectators find it difficult to empathise with. As one interviewee in our Uefa-funded research of referee abuse in France and the Netherlands explained:

I play football and am also a referee. From my experience, players, supporters and coaching staff don’t see refs as people, and tend to regard them as outsiders. I don’t think they realise how integral they are to allowing games to go ahead.

Whether commenting on social media or shouting abuse from a crowded stand, the failure of people to recognise referees as “real human beings” is a recurring theme of our research. There is little understanding of the impact that abuse can have on an official’s mental wellbeing. As one grassroots referee told us:

In football, it is culturally acceptable to question referee’s decisions and to shout and swear at them. Players do it, and so do spectators at all levels of the game I have observed and worked in. Abusing the ref is standard at the highest levels in football and is even common in youth football. It is a short step from questioning a decision to shouting abuse.

The growth of social media and presence of online communities has compounded the sense that referees are “fair game” for criticism – without fear of any comeback. For spectators both virtual and real, abuse of officials can become infectious, as this experienced referee told us:

Where there are larger groups of people, the herd mentality sets in. There are people that in my mind would not normally make any abusive gestures towards anyone – yet it is often deemed as acceptable [when they] attend games … because, in all likelihood, they would never get caught. As they have no personal connection to the official in charge, they feel no or little remorse.

The (bad) influence of the professional game

The frequent abuse of referees in the professional game is seen as a major contributory factor to problems lower down the football pyramid, as players and spectators take their lead from the behaviour they see in stadiums and on TV.

In one shocking recent example, Turkish referee Halil Umut Meler was punched to the ground after the final whistle of a game in Turkey’s top professional league, putting him in hospital treatment with injuries including a small fracture under his eye. His attacker, the president of one of the clubs contesting the game, was subsequently arrested and banned from football for life.

Ali Unal/AP/Alamy

The eye-watering increases in television and sponsorship income, as well as prize money, means the pressure on professional football clubs to be successful has perhaps never been greater. As such, decisions made by referees over the course of a season, and particularly in the final stages of league and cup competitions, are increasingly being identified by clubs as a reason for falling short.

Near the end of the most recent Premier League season, Nottingham Forest claimed on X after one defeat that the game’s video assistant referee (VAR) was a fan of rival club Luton Town – insinuating that this was a reason for their loss, and inflaming the anger of Forest supporters towards this official.

Ironically, the introduction of VAR technology was seen as a way of protecting referees from making “clear and obvious errors” – yet many argue it has, in fact, only increased the pressure on referees and pushed them further into the spotlight.

In a press conference after a victory for his Tottenham Hotspur team that was decided by a VAR error, Spurs manager Ange Postecoglou highlighted the need to remember the humans at the heart of every match decision – even those made many miles away by VAR officials:

The game is littered with historical refereeing decisions that weren’t right, but we all accepted it was part of the game because we’re dealing with human beings … But now I think that people are under the misconception that VAR is going to be errorless. I don’t think there’s any technology that can do that because so much of our game isn’t factual. It’s down to interpretation, and they’re still human beings.

What can be done to stop the abuse?

Changing this culture of abuse is key. Coaches have an important role in setting an example and enforcing codes of behaviour for their players. I strongly believe the vast majority of officials are doing a difficult job as well as they can – and they deserve our respect accordingly. (Grassroots football coach)

Many referees would like to see more education of players, fans and club officials – to remind them that, far from being a hindrance, grassroots referees are people who give up their time to enable everyone to enjoy the game. As this amateur referee explained:

It’s important to remind everyone that sports at levels below professional competition are refereed by part-timers. They are, by and large, refereeing on their own and do not have the luxury of a linesperson to help monitor for offside. They have no VAR to give them an opportunity to review an incident. They will not and cannot see every infringement. Too often spectators and players forget this.

But many referees also want more of a “stick” to eradicate abuse. Our research found that only a third of football referees surveyed across Europe, North America and Oceania were satisfied with the sanctions handed out after they had reported being abused:

I think football needs a whole culture change so it’s like rugby, where you are not allowed to argue with officials. But maybe refs also need to be stricter with punishments for dissent … In basketball, if you argue with referees, you are given a technical foul and fine, and that may be something that would limit arguing in football. (Grassroots football referee)

In 2017-18, English amateur football piloted use of the “sin bin”, whereby players were temporarily removed from play for up to ten minutes if they abused a referee or their assistants. This trial was then extended to 31 amateur leagues across England, with suggestions that sin bins could be introduced in professional football along with a blue card to denote a player being temporarily sent off.

One grassroots woman referee explained how she uses sin bins to de-escalate potentially difficult situations:

I think having sin bins is quite helpful. When I referee men, I find the captains are quite good – you can talk to them and they will usually sort their team out. You can kind of deal with it that way [without actually having to send players to the sin bin].

However, the International Football Association Board, which determines the laws of the game, has completely rejected the blue card proposal, demanding further evidence on the effectiveness of sin bins while trialling other ideas to improve the behaviour of professional players. These include proposed “cooling-off periods” which would see referees send teams to their respective penalty areas if behaviour is judged to be becoming too heated.

Football is not alone

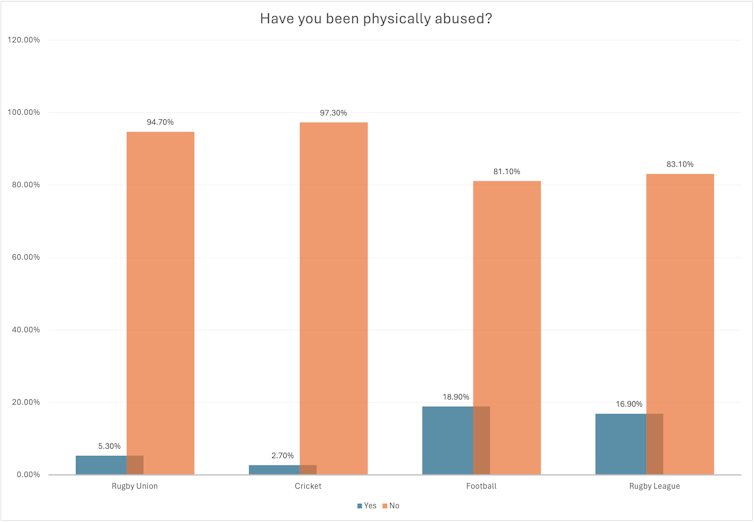

When it comes to referee abuse, football is far from alone in having a problem. Over half of the officials we surveyed across rugby union, rugby league and cricket reported being subjected to abuse and aggression. This account of refereeing abuse comes from grassroots rugby league:

When I was refereeing, I was confronted by a coach from an away team. The coach entered the field of play and aggressively shouted in my face about a decision I’d made, calling me an ‘inconsistent fuck’. Given the situation, I had to dismiss the coach, which led to the game being abandoned since they didn’t have another coach. Following the abandonment, I faced a barrage of insults and gestures from the majority of the away team’s players, who chanted ‘cheating wanker’ and gestured the ‘wanker’ sign towards me.

This referee, who was 18 at the time, said the experience “took a massive toll” on his confidence and mental wellbeing:

During a subsequent academy match I was touch-judging, the anxiety from the previous incident impacted my performance, culminating in a panic attack that prevented me from continuing in the second half.

While this referee has since restarted their career and is aiming to reach the top of the professional game, many others do not restart after such experiences.

Rates of verbal and physical abuse reported by referees at all levels of four sports, England:

Tom Webb/Research Centre for Business in Society, CC BY-NC-SA

Tom Webb/Research Centre for Business in Society, CC BY-NC-SA

Even rugby union, which is traditionally associated with players calling officials “sir” and accepting decisions without question, is wrestling with how to eradicate growing levels of abuse at all levels of the game.

After rugby union’s 2023 world cup final between New Zealand and South Africa, the match referee, Wayne Barnes, and his family were subjected to death threats including that their house would be burned down. Barnes subsequently retired from refereeing, a decision he said was influenced by the “threats that have become far too regular for all of those involved in the game”.

In both rugby codes, the behaviour of spectators and players is a growing concern at all levels. To help recruit and support young referees in rugby league, for example, head cameras known as RefCam have been introduced to monitor the abuse they receive.

Christophe Ena/AP/Alamy

Abuse of young referees

Young referees in any sport are learning, just as players are learning. Yet according to some club officials we have spoken to, abuse is often worse towards these young officials than adult referees:

I coach youth [rugby league] with regularly young referees. I believe they are more at risk of verbal abuse due to their age and experience, and find parents are less abusive towards older referees. These young referees need protecting more to reduce the damage to their self-esteem, ability and desire to come back to referee the sport.

There are, first and foremost, child protection considerations with young referees if they are receiving abuse from adults. I (co-author Tom Webb) have coached in youth sport myself, and seen referee abuse first-hand from coaches, players and spectators. When the behaviour is challenged, invariably the coaches don’t see what they have done as wrong, or they do not care.

This abuse is often adults behaving negatively towards young referees who have recently qualified and are under 18. This presents a clear safeguarding issue, yet in the context of football, abuse towards child referees appears to be widely considered “part of the game”.

Parents of young referees complain that safeguarding rules are not being followed by sports’ governing bodies, and that the processes of complaint – in particular, children having to attend personal hearings with the adult coaches or spectators they have complained about – make it much harder for them to report abuse.

Igor Stevanovic/Alamy

At the same time, we have also heard positive accounts of the value of mentorship schemes, such as from this young female football referee:

As soon as I turned 16, I had a men’s game and I’ve never received so much abuse in my entire life. But because I had a mentor, I’d sort of built myself up to it, so that’s why I continued. I spoke to them about it, and my county [association] was really good as well. If I have any issues, it goes straight to the county and they sort it out and help you. I’m fortunate that I’ve had that stability.

What can be done to halt the abuse?

Our recent research into the recruitment and retention of female sports officials across Europe shows they believe they receive less abuse than their male counterparts. However, the abuse that female officials face is still evident and, like their male counterparts, makes them much more likely to quit their chosen sport.

Abuse is threatening the very structure of organised, competitive sport. As the number of fixtures without neutral referees increases, so grassroots sport becomes ever harder to administrate and operate effectively.

The aim of reducing or eradicating the abuse towards referees should be a primary focus for sports organisations around the world. Supporters’, players’ and coaches’ better understanding the laws of a sport could help acceptance around why a decision is made by a referee during a fixture. But this alone will not reverse the recruitment and retention issues in refereeing.

Based on our research, we believe the focus needs to be two-fold: reduce the abuse levels by changing the culture towards referees in sport; and ensure the systems are in place to support referees and punish offenders adequately when abuse occurs.

We cannot be naive enough to think that abuse towards referees can be removed entirely from competitive sport. The question is, do sports organisations have the sufficient will to affect change and significantly reduce abuse?

From our two decades studying this issue, we can say that most sports have been far too slow to address this endemic issue. There are, though, finally signs of a willingness to confront the problem – driven in part by growing awareness of the problems of recruiting and retaining referees that these organisations face.

But for any recruitment drives to succeed, there must be a cultural change that raises the profile and importance of sports officials – and above all, addresses the shocking treatment of our young referees. Without this, we believe many sports – not only football – could face a severe shortage of grassroots officials, and subsequently elite-level referees. As one rugby union touch judge reflected to us:

Near the end of one game, I was subjected to a torrent of abuse from a handful of drunken adult male home supporters. The statements made towards me on repeat for that 20-minute period were: ‘You’re a fucking cheat, touch judge! You cheating cunt, touch judge!’ After almost 30 years of officiating, I have pretty tough skin. But it did make me wonder why I bothered doing this when I could be with my family. Instead, I had a bunch of drunken men abusing me.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.