China’s involvement in Horizon Europe is becoming increasingly restricted to environment-focused and basic research, but is still holding up despite geopolitical headwinds and the disruption to face-to-face contact caused by the pandemic, a Science|Business analysis has found.

Cooperation on areas now seen as sensitive, like sensors, databases and the internet has given way to projects in areas like forest management and pollution.

But continued Chinese participation could soon take a hit after the European Commission this year banned China-based researchers from joining close-to-market research calls.

Yet at the same time, two Horizon Europe flagship projects – on climate and biodiversity, and food, agriculture and biotechnology – have deliberately brought Chinese and EU researchers together. Both sides pay for their own involvement in joint projects, although this has caused problems in signing off grants at the same time.

“In my own experience, cooperation has to deal with increasing difficulties,” said Blas Mola-Yudego, a researcher at the University of Eastern Finland, who is part of eco2adapt, a forestry resilience project involving six Chinese partners that started last year.

Post-pandemic travel restrictions, difficulties using software in China, and troublesome visa procedures have all made collaboration harder, Mola-Yudego said. “However, I feel a strong will to keep working together.”

Over the past few years the European Commission has been trying to recalibrate its research relations with China to avoid passing over sensitive technological or even military knowhow. This followed years of concerns over intellectual property theft, and worries that European researchers had been naively helping Chinese counterparts with military technology.

In 2021, a major policy document, the Global Approach to Research and Innovation, warned that China’s position as “an economic competitor and a systemic rival to the EU calls for a rebalancing of research and innovation cooperation.”

This policy pivot hasn’t always been watertight. In May, a Science|Business investigation reported that the EU was still funding five ongoing, potentially dual-use research projects with Chinese universities linked to the military, including one project agreed under Horizon Europe itself.

Chinese participation holds up

Perhaps surprisingly, this cooling of relations hasn’t led to a drop off in Chinese participation, at least not just yet.

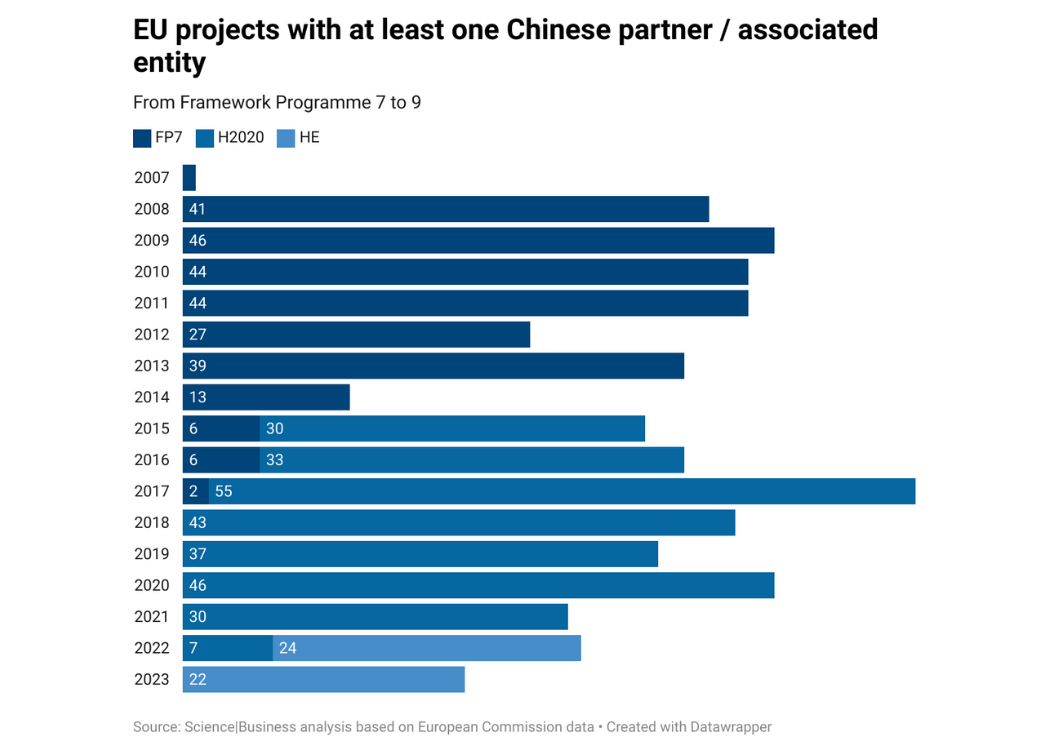

In the two and a half years since Horizon Europe started, Chinese entities have joined 45 projects, according to an analysis by Science|Business.

During the equivalent period of Horizon 2020, which started in 2014, China was involved in 50 projects – so if anything, Chinese involvement is flatlining.

However, Chinese participation in FP7, the framework programme that ran from 2007 to 2014 had much stronger Chinese participation at the beginning. During the first two and a half years of that programme, China joined 82 projects. But that was a period when relations between Beijing and Brussels were much more cordial, and the Commission was doling out money directly to Chinese universities, rather than expecting that the Chinese fund their own share.

A green hue to research collaboration

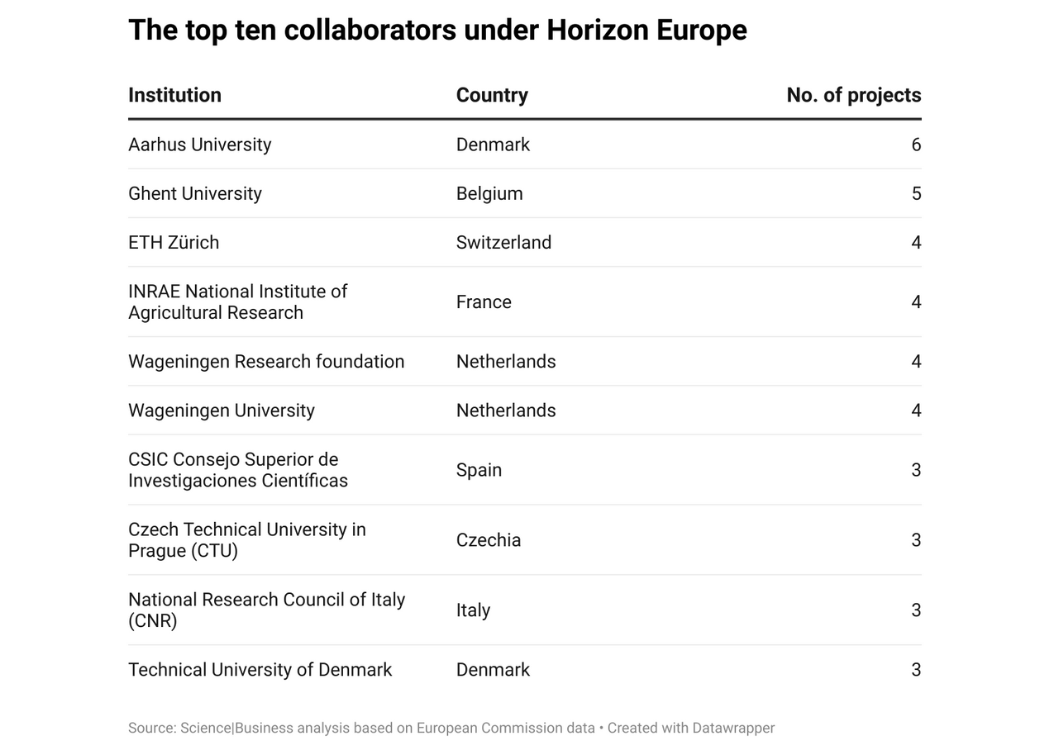

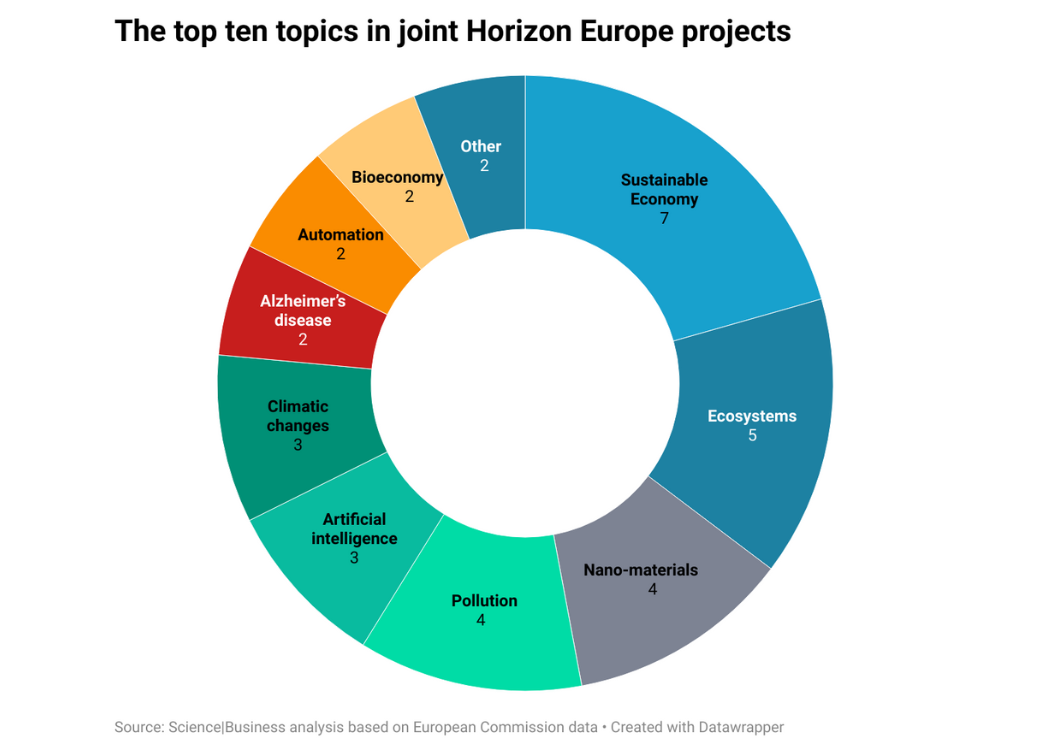

Under Horizon Europe, collaborative projects with China have a distinctly green hue, concentrating largely on areas like the sustainable economy, climate change, ecosystems and pollution. These are exactly the kind of China-appropriate, saving-the-world-together topics the Global Approach envisages, rather than anything that could be considered technologically or military sensitive.

Under the two previous framework programmes, potentially touchy technologies like sensors, databases and the internet were among the top ten most investigated topics (although eco-research was also a common theme). But under Horizon Europe, these areas have fallen out of popularity.

Still, there are a handful of projects funded under Horizon Europe that have a computing or industrial focus, as opposed to an ecological one.

As previously reported, the EU is funding the HyQuArch project, a joint attempt between a Spanish research institute and the University of Science and Technology of China – which has quantum defence links – to create a “novel hybrid quantum architecture”.

Another consortium involving two Chinese universities is investigating how to print nanomaterials that change shape over time. And Chinese institutions are also involved in another project to research AI-powered autonomous vehicle systems.

Innovation Actions

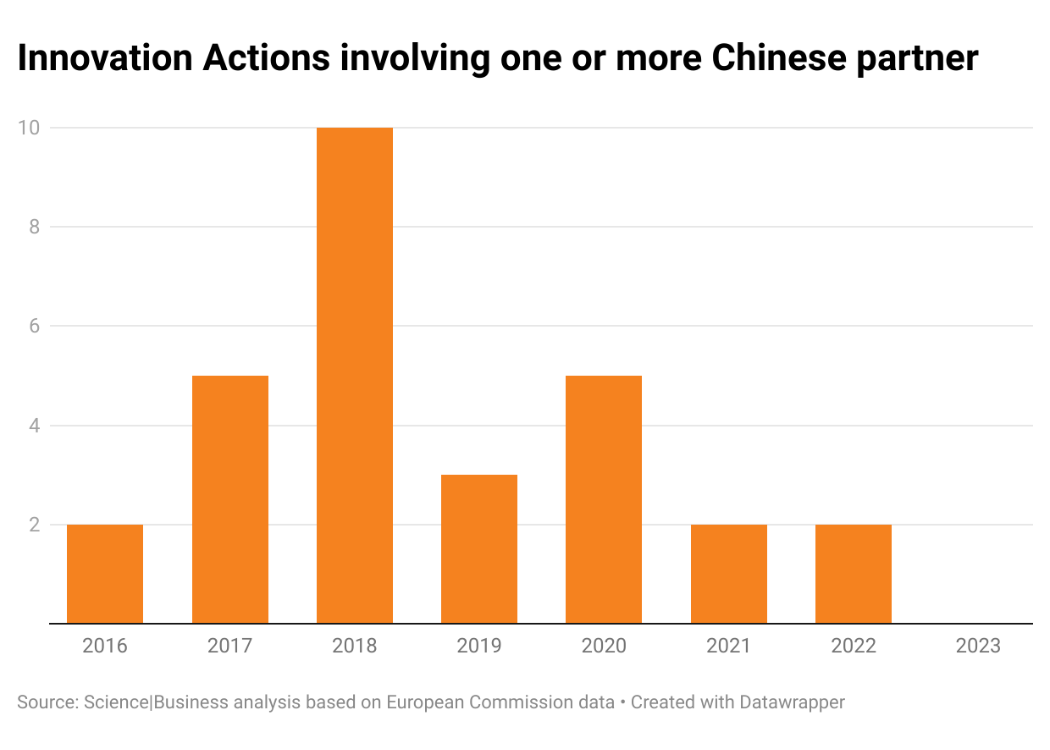

Although collaboration with China appears to be holding up so far, a big policy change this year could slow things down.

Since the beginning of the year, the Commission has excluded any Chinese entities from taking part in so-called Innovation Actions: close to market projects developing new or improved products, for example through prototyping, testing or demonstration.

In the view of the Commission, talks between Brussels and Beijing to establish a “level playing field” in science, technology and innovation haven’t made any progress, at least in the field of innovation.

Chinese entities are therefore not eligible to take part in Innovation Actions “in any capacity”, according to the latest Horizon Europe work programme, which sets out grant calls to be made in 2023 – 4.

“Exceptions may be granted on a case by-case basis for justified reasons”, it adds. But any exemptions would be spelled out in the work programme, a Commission spokesman said, and as it stands, in 2023-4, there are none.

This exclusion from Innovation Actions cuts China out of a big part of Horizon Europe. In the latest work programme, such actions make up a quarter of all calls, according to a Commission spokesman.

And during Horizon 2020, China was a regular participant in Innovation Actions – they made up one in ten projects with Chinese participation.

Excluding China from these close-to-market calls gets particularly controversial when it stops Chinese researchers from joining projects addressing climate change, one of the few areas in which the EU is still keen to collaborate.

For example, China is shut out of a €15 million forthcoming project to create new ways to capture carbon dioxide, for example, by scrubbing it directly from the atmosphere.

Critical raw materials

China is also effectively banned from 11 proposed projects to find ways for the EU to better secure critical raw materials – the rare earth magnets that go into electric vehicle engines or wind turbines, for example.

The Horizon Europe work programmes that detail these projects don’t explicitly exclude China by name, but are drawn up in such a way to include practically every other country.

This exclusion is hardly a surprise. Brussels is worried precisely about its dependence on China for certain materials, like rare earth elements. Restricting who can take part should avoid “reinforcing existing over-dependencies, as well as the importance of involving partners committed to pursuing open trade in such materials,” the calls say.

Flagships set sail

In contrast to these exclusions, there are parts of Horizon Europe where Chinese scientists are positively welcomed.

Two so-called flagships – big, long-term research efforts comprising clusters of grant calls – are specifically aimed at consortia involving researchers in the EU and China. One covers climate change and biodiversity, which was agreed in 2021, and the other food, agriculture and biotechnology, which has been going since 2013.

One key theme is the nailing down of joint climate models, data and measurement tools that can be used by both sides. For example, one call, for which proposals are currently being evaluated, aims to create a joint EU-China framework that models how both countries get to carbon neutrality by the middle of the century.

Another, looking at the “blue carbon” locked away in seagrass, salt marshes and mangroves, plans to create new measurement techniques to better understand their contribution to greenhouse gas emissions.

So far, four calls are in the evaluation stage, three have not yet opened to submissions, and four have already been awarded.

No more EU funding

It’s important to note that now, the Commission only funds EU partners. Chinese partners need to get their own money from the country’s Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST).

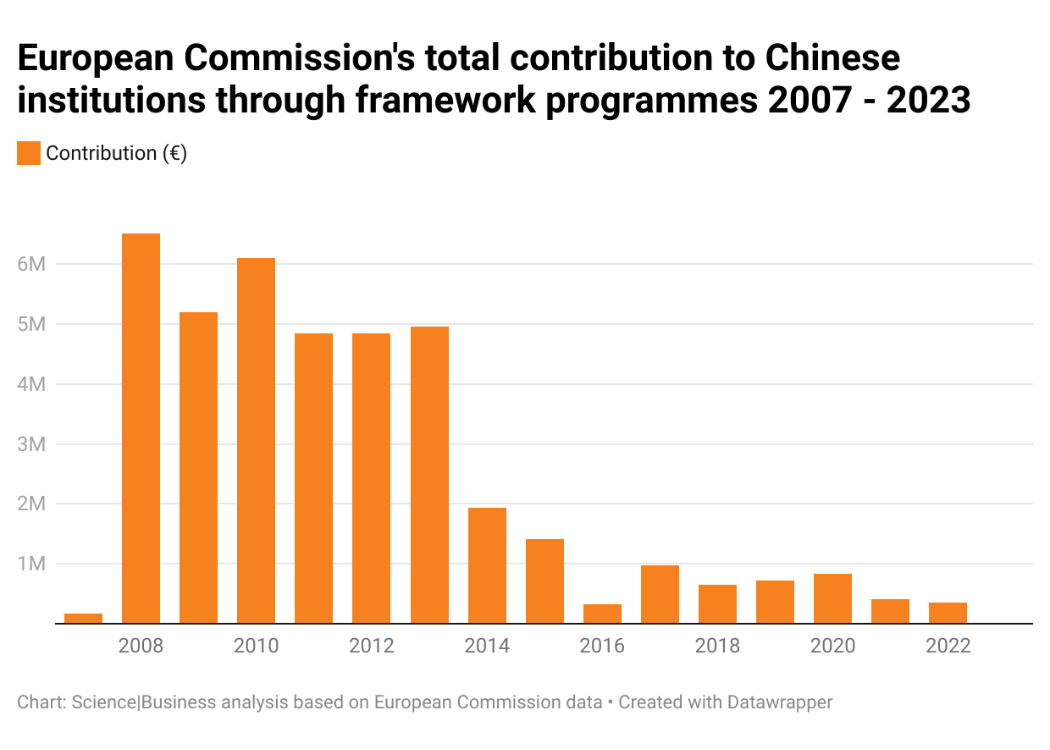

This is a far cry from the late 2000s and early 2010s, when the Commission used to pump millions of euros of its own money into Chinese research institutions. This seems inconceivable in the tense, suspicious geopolitical environment of 2023, but under the rules of FP7, which ran from 2007-13, China was included in a group of low and middle-income countries that were eligible for funding from the Commission.

That changed in 2014 under Horizon 2020. China, along with other states including India, Russia and Brazil, were removed from this group, and so direct EU funding started to dry up.

Splitting funding for these joint projects between the EU and China brings its own problems, however.

For one awarded project, EcoNutri, which aims to cut water pollution and fertiliser use in farming, China’s MOST still hasn’t signed off funding for the Chinese side, despite the European partners having commenced work nine months ago, said Dimitrios Savvas, a professor at the Agricultural University of Athens, who is coordinating EcoNutri.

“This certainly causes some problems in coordination,” he said. The Chinese scientists were absent from the project’s kick-off meeting, although he stressed that otherwise communication with the Chinese side has been good.

Coordination problems

The problem is that the release dates for project guidelines and call for proposals are not yet synchronised between China and the EU, said Changlin Gao, Minister Counselor for Science and Technology at China’s Mission to the EU, drawing on his conversations with officials at MOST responsible for co-funded programmes.

“In order to improve this problem, the Chinese side has made great efforts to synchronize with the European side in the new round of calls,” he said.

Similar coordination issues have hit trans4num, another funded project focusing on nutrient management in agriculture.

The project started at the end of last year, but the Chinese partners were only approved in June, said Andrea Knierim, an agricultural researcher at the University of Hohenheim who is coordinating trans4num. But still, the Chinese partners have been closely involved in the process otherwise, she emphasised.

The Chinese side is also waiting for approval to join the Agriloop project, an effort to convert farming residues into plant proteins, polyesters and chemicals, said Aimin Shi, a researcher at the Institute of Food Science and Technology in Beijing.

Personal data

Some of the EU partners on EcoNutri were also initially rather perturbed by Chinese requests for personal data – including home addresses, mobile phone numbers and passport numbers – said Henrique Trindade, an agricultural researcher at the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro in Portugal.

They were told that it was necessary in case researchers on the EU side visited China for a project meeting, he said.

Gao, having spoken to officials at China’s MOST, said that this data was requested “to ensure the authenticity of the application for cooperation projects between China and the EU”.

“It is absolutely necessary to provide the personal identity information of the PI [principal investigator],” he said. “The Chinese PI will also provide necessary personal information to the European side.”

China wants more partnerships

Now several years of pandemic travel restrictions are over – China only ended quarantine requirements for inbound travellers in January – Chinese officials are now keen to create new green-focused research partnerships.

“With the pandemic gradually waning, the situation has improved significantly,” said Xian Zhang, an official at China’s MOST working on Agenda 21, a sustainable development initiative.

This year, he has visited Germany, plus Cambridge University, Imperial College London, and University College London in the UK to discuss cooperation on areas such as climate change, artificial intelligence, carbon capture and storage, and monitoring carbon emissions.

Geopolitical headwinds, and the inability to meet face-to-face during the pandemic have “introduced some new considerations” in the relationship with Europe, Zhang acknowledged.

Yet overall, he’s upbeat. “Looking ahead, I would like to see more bilateral visits between China and Europe and foster a cooperative environment for China-EU science and technology cooperation.”

But apart from in the sphere of environmental research, EU officials are likely to be rather more cautious.