By 1941, as most European states were under the yoke of authoritarian or fascist regimes, and Nazi troops had just occupied France and were moving towards the Soviet Union, Altiero Spinelli (1907-86) and Ernesto Rossi (1897-1967), two Italian antifascists, were envisioning plans for a federalist and democratic Europe based on a European constitution. Spinelli and Rossi wrote a tract calling for a federal European union while they were political prisoners of the Fascist Mussolini government, held on the small penitentiary island of Ventotene in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. Their Ventotene Manifesto, actually entitled ‘For a Free and United Europe’, called for instituting a European federation with a democratic government and parliament with real sovereign powers regarding economic and foreign policies.

Spinelli attempted twice to achieve a European constitution based on a federal union. His first effort came in 1954, when the French National Assembly refused to accept a treaty, and then in 1984, when the European Parliament approved – but then the United Kingdom rejected – the Draft Treaty establishing the European Union. Instead of a European constitution, in 2007, member states signed the Lisbon Treaty: an inter-governmental treaty regulating the process of European integration. The Lisbon Treaty and Spinelli and Rossi’s plan show us two different models of European integration: a technocratic and a democratic approach. Spinelli’s democratic project was elaborated and approved by the European Parliament, which acted as a constitutional assembly. The Lisbon Treaty’s technocratic one is an agreement between European governments, characterised by long and secret negotiations and compromises.

The 1993 establishment of the European Union (EU) did not resolve the tension between a technocratic and a democratic Europe, and the advent of a European constitution is still more a dream than a concrete political project. In reality, the EU remains at the crossroads between the ‘Europe of the people’ and the ‘Europe of the governments’. Since the 1957 Treaty of Rome instituting the European Economic Community (EEC), subsequent agreements including that of Maastricht (1992) and Lisbon (2007) have further separated the economic and political aspects of European integration. Remembering how the idea of the ‘United States of Europe’ emerged can help in conceiving of its future prospects and finding answers on where we should go. In the mid-20th century, when Spinelli began calling for a European federation, he was carrying on a legacy of a circle of radical 19th-century Italian political activists who were the first to think seriously about a political project of a ‘United States of Europe’. These Italian radicals envisioned a democratic political project aiming at the freedom and solidarity of all European peoples.

In the early decades of the 19th century, a number of Italian nationalist projects flourished, and their advocates were not confined to Italy. Italy as a nation-state did not yet exist, rather the Italian peninsula was a cluster of smaller and more isolated (and often dominated) states: the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, under the control of the Habsburg Empire, the Papal States, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Giuseppe Mazzini in the early 1860s. Photo courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

Italian radicals still had to imagine a united and independent Italy and, when they did, they conceived of it within a wider project of a European federation. They saw a harmony between national unification and international emancipation possible within the creation of what the Italian republican Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-72) called a ‘Europe of the peoples’, rather than the ‘Europe of the crowned heads’. The latter term, for Mazzini, characterised the state system that emerged in Europe since the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15. He meant it to capture the securitisation of the Old Continent, which restored Europe’s royal families to the thrones they held before the great disruption of the Napoleonic wars. On the other hand, a ‘Europe of the peoples’ was a continent of citizens instead of subjects, of rights instead of treaties, of assemblies instead of monarchies, of political participation instead of economic regulation. Mazzini is one of three 19th-century Italian radicals, along with Princess Cristina Trivulzio di Belgiojoso (1808-71) and Carlo Cattaneo (1801-69), whose lives and work reveal a little of how different the EU would seem to some of the first modern intellectuals to imagine a united Europe.

The experience of persecution and exile connected them with an international society of activists across Europe

Mazzini, Belgiojoso and Cattaneo all experienced exile, inside or outside the current European borders, persecuted because of their political beliefs. They all wrote about a united Europe while also reflecting on the question of borders, in their case, Europe’s eastern borders. These 19th-century Italian republicans did not see a contradiction between the project of an independent, united Italy and that of a European federation of states. Political persecution of radicals by absolutist governments caused them to flee, which initiated them into a process of Europeanisation of political activists across the continent. Many of these 19th-century radicals spent most of their lives in exile.

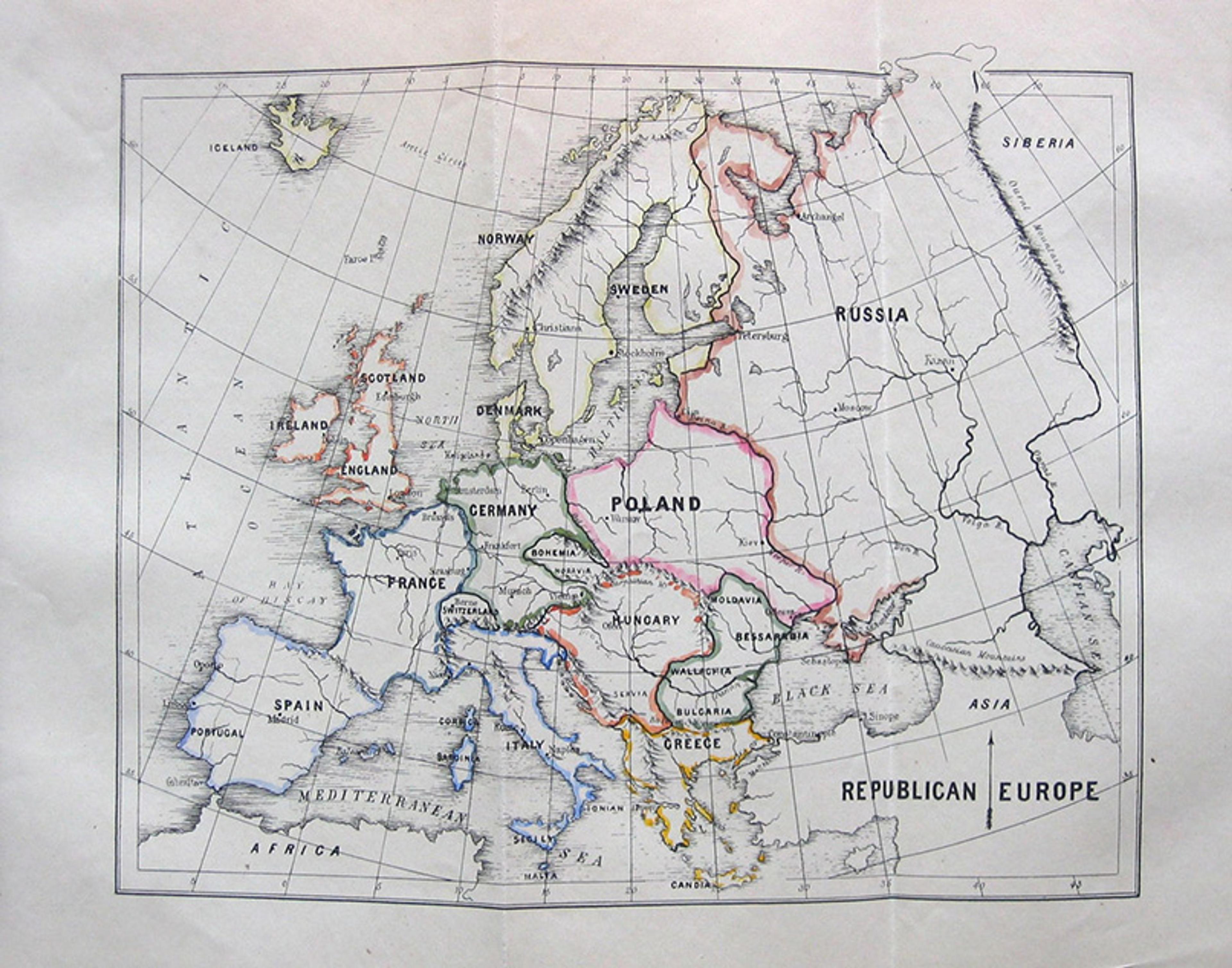

‘A Map of Republican Europe’ (1854) from William James Linton’s English Republic. Linton was an artist and political reformer, as well as a great admirer and friend of Mazzini. Courtesy the Melton Prior Institute, Dusseldorf

The experience of persecution and exile connected Italian republicans with an international society of activists across Europe. Together, they created secret societies, the most notable and widespread being Young Europe, founded in 1834 by Mazzini. Young Europe organised and coordinated the resistance to absolute powers in different European countries, including the Italian and the German states, Poland, Hungary and Ukraine. Young Europe often promoted clandestine operations and circulated subversive ideas, and they imagined the United States of Europe’s borders extending east to include Ukraine and Turkey, where Belgiojoso spent a long period in exile. These Italian radicals envisioned a larger and more democratic Europe than the one we have come to know through the EU, one shaped by their experiences in exile.

It was 1836, and police searching a small student apartment in Kyiv found forbidden books and manuscripts that led to the identification of organised political groups across Ukraine. Part of an intensified programme of vigilance, the tsarist police were looking for underground networks that were proliferating among radicals and republicans. In the spring of 1836, the charismatic Polish soldier-political activist Szymon Konarski (1808-39) had visited Kyiv and inspired the foundation of revolutionary cells across the country. Konarski had been one of the leaders of the Polish November Uprising against the Russian Empire (1830-31). In the wake of its defeat, he had fled the country, exiled to Switzerland. Konarski worked hard to recruit activists to the ranks of Young Poland, the Polish branch of the secret society Young Europe. He was remarkably successful in winning non-Poles to the cause, in part because the regime of Tsar Nicholas I tended to criminalise and punish even the most innocent complaints.

In an environment where opportunities to express dissent were so narrow, repression had a channelling effect, pushing the discontented of all groups toward the few activists whose networks remained intact. In the second half of the 1830s, Konarski became the leading conspirator in Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania, while also fulfilling his mission on behalf of the secret society Young Europe. Konarski’s sponsor was Mazzini, one of the chief leaders of the Italian movement for unification and independence. Konarski had met the Italian patriot while in exile in Switzerland and quickly became a passionate advocate for Young Europe as well as someone whom Mazzini trusted to represent those ideals in eastern Europe.

When Mazzini fled Italy in 1831, the Italian Peninsula was home to a number of dissociated states, most of them under direct or indirect Austrian influence. The Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia remained an Austrian province. Arrested for being a member of the secret society Carbonari, Mazzini was absolved for lack of evidence but forced to leave the country. In 1831, while in exile in Marseille, he founded the patriotic organisation Young Italy, which expounded the view that ‘Italy [was] destined to become … one independent sovereign nation of free men and equals.’ Young Italy served to coordinate, throughout the various Italian states, insurrections against foreign domination. After lobbying by the Austrian ambassador in Paris resulted in their expulsion from France, Mazzini and his associates fled to Geneva in the summer of 1833. At around the same time, several hundred Polish officers, fleeing prosecution after their involvement in a failed uprising in Frankfurt, sought a haven in the Swiss Confederation. For a few short years, Switzerland transformed into a laboratory for building a transnational nationalist movement. Mazzini lived a more or less clandestine existence there until he was expelled from the country for his participation in the revolt in Genoa. In 1837, he moved to London, where he would spend the greater part of his life.

European brotherhood, Mazzini believed, would arise through a process of cultural and civic integration

Mazzini believed that independent and democratic republics were a united Europe’s proper constituent parts. His Europeanism took on more precise political connotations in Switzerland, where he was thrust into the cosmopolitan world of political émigrés and mingled with exiles from Poland, Germany, Italy, Russia, eastern Europe and Scandinavia. Mazzini’s plan was to create a network of associations similar to Young Italy across Europe: Young Poland was founded in late 1833, and Young Germany around the spring of 1834. These ventures led to a more ambitious plan: on 15 April 1834, in Bern, Mazzini constituted Young Europe, incorporating refugees from Italy, Poland and Germany.

Mazzini’s activism for democracy came to encompass a political project of European scope, anchored in parallel national revolutions, coordinated in solidarity through the good offices of Young Europe. Members of Young Europe represented a wide cross-current of republican thought and practice from all over Europe. By swearing the Oath of Allegiance, the republicans who made up the society undertook to tackle together the political and military challenges they faced in their respective countries, pooling the insights they had won through their experience of defeats and failed insurrections.

Young Europe was one of the first transnational political associations that aspired to realise a new political order based on democracy and national self–determination. Mazzini used the republican language favoured by secret societies of the early 1830s to advance the European project. To the hierarchical dynastic geography of the old Europe, Mazzini opposed a youthful egalitarian republic of equal states. European brotherhood, he believed, would arise through a process of cultural and civic integration (though Mazzini was rather vague on the question of exactly how this would occur).

Young Europe’s proposal of a ‘holy alliance of the peoples’, replacing the alliance of kings, appealed to the Poles. They were efficient disseminators of Young Europe’s ideas among the Slavs in eastern Europe. They also educated Mazzini on eastern Europe’s nationalist movements. Mazzini was in contact with numerous influential Poles, including the historian and activist Joachim Lelewel (1786-1861), leader of the Polish democrats in the Polish National Committee, and mentor to Konarski, who also was very close to Mazzini and his European cause.

Mazzini thought that democratic nationalism could win national, social and political freedoms within a democratic united Europe. It was a federalist project for Europe, developed in close dialogue with nationalist movements in eastern Europe. He believed that revolutionary national movements across Europe could achieve democracy and national self-determination, and then form the foundation for an alliance of free peoples. Mazzinians envisioned a United States of Europe with borders stretching to Ukraine.

Belgiojoso also envisioned ‘A Europe of the People’, a federation of democratic nation-states that she saw including Turkey. Her wealth allowed her to live beyond the roles of mother and wife, engaging in politics, journalism and scholarship. In 1828, after separating from her husband at the age of 20, she left her home in Milan and started travelling, moving first to Switzerland and then to France, where she lived up until 1840. She would spend most of the rest of her life in exile.

In Paris, Belgiojoso hosted a renowned salon and became the chief port of call for Italian exiles and a focal point for Parisian intellectual life. In 1838, she gave birth to her daughter Maria (father unknown), curtailed her social engagements and, in 1840, returned to her native Lombardy. There she organised her properties with a view to improving peasants’ living conditions. She built housing and dining halls where food was served at subsidised prices. She founded nurseries, primary and secondary schools for boys and girls, offered free healthcare and built a large, heated room in which to take refuge during winter. Inspired by Mazzini’s ideals, her aim was the realisation of a democratic republic that would take care of the ‘poorest and largest class’. Belgiojoso’s political thoughts and actions were mostly characterised by an attentiveness to the plight of the lower classes. In her judgment, they would be the key element guiding political action, so, naturally, the health of a political system depended on their wellbeing.

In 1849, Belgiojoso had been involved in the defence of the Roman Republic, a revolution aimed at achieving Italian unification and independence. She funded and led the revolutionary government’s Committee for Assistance to the Wounded and, with other women activists, including Enrichetta Di Lorenzo (1820-71) and the American Margaret Fuller (1810-50), organised hospitals to tend injured revolutionaries and civilians. After the defeat of the Roman Republic by the French army, Belgiojoso travelled east to the Ottoman Empire. She also wrote about her democratic ideals, publishing in journals on current affairs as well as contributing essays on the 1848 revolutions on the Italian peninsula.

After the suppression of the 1848/49 revolutions, the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Abdulmejid I (1823-61) offered a refuge for many European radicals forced to flee. The exiles came mainly from the Austrian lands – they were Italian, Polish and Hungarian, and their presence caused diplomatic tensions with the Habsburg and Russian empires.

In a harem, Belgiojoso saw how an isolated life could limit psychological development and self-determination

In the summer of 1850, Belgiojoso’s arrival from Italy interrupted the monotonous life of the small village of Çakmakoğlu, in central Turkey. The inhabitants of this village far from Constantinople particularly admired the exotic Italian furniture Belgiojoso brought with her. She travelled with her 12-year-old daughter and her English nanny, Mrs Mary Ann Parker. Local people soon became attached to Belgiojoso, who wanted to live off the land and was knowledgeable enough about medicine to offer good advice. When she had no money, she lived on credit. She was so liked that nobody ever asked for the money back. On this journey through Ottoman lands, she developed a conviction that a united and democratic Europe was possible.

Belgiojoso published, in French, accounts of her Ottoman exile, focused on the everyday life of the Turkish lower classes. Importantly, her accounts avoided the mystery and exoticism typical of 19th-century European Orientalism. Belgiojoso had retained her interest in understanding the social and political life around her and in particular the daily life of the poorest and most oppressed, offering the readers of the Parisian Revue des Deux Mondes narratives of life in the Ottoman village, which hold up well and distinguish themselves from the more biased accounts that western Europeans typically produced of life in the Ottoman Empire.

For example, Belgiojoso gave readers a valuable description of the institution of the harem. As a woman, she was able to gain access to the harem interior and make real observations (rather than the fanciful scenes in the manner of The Thousand and One Nights that were the stock-in-trade of Orientalist fiction and memoir). She saw how an isolated life could limit a person’s psychological development and their self-determination. Her attention to domestic spaces and women’s subordination would also enrich her essay on Italian women, ‘On the Present Condition of Women and on their Future’ (1866). Here she highlights the key role of education in promoting equality between men and women, while insisting on the need to avoid radical and sudden change in the condition of women in the newly formed Italian state.

While observing the reality of women’s lives in the Ottoman lands, Belgiojoso examined the ‘national character’ of the Turkish people. In praising their gentleness, she insisted that these qualities were to be found mainly in the lower classes living in the countryside or in provincial towns, and not in the urban upper classes. Belgiojoso reflected on the nature of the relationship between Europe and Turkey, a matter of pressing concern, given that she was writing during the Crimean War. Europe’s fundamental task, she maintained, was to preserve Ottoman independence. She insisted that Turkey ought rightfully to be considered part of the ‘concert of the European nations’. In time, Belgiojoso insisted, Turkey could become ‘the richest, as it is already the most beautiful [country] in the old world’.

While Belgiojoso sought refuge deep within the Ottoman lands, Mazzini was in constant contact with exponents of the eastern European nationalist movements. The United Europe they both envisaged included Ukraine and Turkey. Their experience and observations informed a vision of a federal unification in which centralised national republics united against the tyrannies of absolute monarchs and emperors. Not everyone was impressed by this vision. Others preferred to focus on local autonomies and federalist solutions. Cattaneo was one of the most eloquent and influential republican thinkers who supported a European federation based on local autonomies. He called it a ‘Europe of the cities’, an idea that he developed by comparison with urban organisations in Asia.

Cattaneo wrote many books on the Far East, all without ever living in or visiting East Asia. When Cattaneo gazed out from the window of his second-floor residence in the Swiss village of Castagnola by Lake Lugano, overlooking Mount San Salvatore, the pleasure he took in this vista of vineyards, fruit and olive trees must have been tempered by some frustration and constraint. This mid-19th-century canton was a quiet place where citizens enjoyed more liberties than in many of the neighbouring countries. Italian exiles had often chosen the Swiss Confederation as a destination, benefitting from its freedom of expression and a pervasive republican culture. Many of them founded newspapers and journals in collaboration with Swiss intellectuals and politicians. Italian patriots, persecuted political figures and refugees found asylum here but also a laboratory for the theory and practice of political liberty. Of Mazzini, Belgiojoso and Cattaneo, it was the latter who had the closest ties to Switzerland, residing there from 1848 until his death in 1869. His time in the country shaped his political ideas for Italy – and for Europe. Cattaneo modelled the democratic federalism of a European government of city-states on the Swiss federation.

As a republican patriot, in March 1848, Cattaneo led the War Council of the revolution in Milan, when the city drove out, in the space of five days, the Austrian troops led by the field marshal Joseph Radetzky (1766-1858). Despite his notoriety, Cattaneo declined to play an active part in the political institutions. When nominated to the Piedmontese parliament, he refused. He also rejected Mazzini’s invitation to become minister of finance in the Roman Republic of 1849, preferring to remain in his Swiss exile, as he was critical of Mazzini’s political projects. Mazzini wanted a unified nation under a republican central government, whereas Cattaneo dreamed of a strongly decentralised and federal mode of unification, based on the autonomy of each municipal community.

Cattaneo saw the self-government of the polis, the dignity of human existence, and the sovereignty of law as the main qualities and components of Europe. The centre of European civilisation was the city, as the political, institutional and urban organisation of public life. He considered the polis in ancient Greece, the Roman Republic and the Italian comuni in the Middle Ages as the loftiest expressions of the European city. Local self-government represented, in his opinion, the principal antidote to tyranny and despotism. Like many in his generation, Cattaneo learned from history that the collapse of the municipal order led to decadence and barbarism. The city was, he wrote, ‘the nation in the most intimate refuge of its freedom’. Cattaneo held it a tragedy of immense import that the process of national unification in Europe was downgrading the city to the ‘last appendage and lowest residue of the prefecture’. Europe, he believed, was following the centralised French national model, to its great detriment.

Cattaneo re-described the ideal of European civilisation, filtering it through a concept of the city

In the centralising government of France, Cattaneo saw a threat to Europe that he believed would undermine the more local practices of self-government that served as the bastion of freedom. Cattaneo also feared that bureaucratic and military centralisation in the French model tended to lead to imperialism and war. He feared that the European peoples would engage in ‘endless wars to usurp a piece of land from neighbouring nations’. Cattaneo thought top-down and centralised forms of government augmented chances for conflict. He identified a close relationship between self-government and the other two pillars of what he called the ‘European spirit’ – the rule of law and the dignity of the individual. Considering the municipal order as the heart of European civilisation, Cattaneo compared this form of political community with other urban organisations in the Far East, which in their gigantic capitals lacked the unity between city and countryside. Cattaneo’s definition of Europe begins with what he considers ‘the Other’ to Europe: Asia.

Cattaneo was interested in how cultural systems interacted with their environments – a field of study he called ‘social ideology’. He wrote books on India (1845), Japan (1860) and China (1861), drawing on a theory that distinguished between ‘stable civilisations’ – closed systems that did not interact with others – and ‘progressive civilisations’ that were open and capable of development. According to Cattaneo, the East, and in particular China and India, contained ‘stable civilisations’ whose destiny was decadence. Such societies were condemned to an inexorable decline, because of a deficient environment for freedom and because despotism stifled everything. Cattaneo believed that the root of the problem lay in the fact that the ‘juridical idea of the citizen’ had not established itself in Asia. The self-governing polis was the principle distinguishing Europe from Asia: ‘municipal order, laws and dignity for citizens’ are at the core of Cattaneo’s idea of the ‘Europe of the cities’. Cattaneo re-described the ideal of European civilisation, filtering it through a concept of the city and its characteristic institutions as the primary form of political organisation.

To Cattaneo, democratic federalism based on the autonomy of municipalities seemed the solution that allowed unity and solidarity among the European peoples to harmonise with their diversity while retaining a degree of autonomy. Cattaneo was sure that a federally reconciled Europe would preserve the continent’s various historical, cultural and linguistic identities but also advance a shared sovereignty that would foster peace and collaboration. In Cattaneo’s words:

We want the unity of the United States of America, not that of England, which oppresses Scotland and Ireland, nor that of Russia, which crushes Poland. We vote for the United States of Italy, but not only for that, but also for the United States of Europe.

Cattaneo wished for a Europe of the cities rather than a Europe of the peoples, as envisaged by Mazzini and Belgiojoso. However, Cattaneo, Mazzini and Belgiojoso all agreed that a unified and free Italy would amount to an enduring and effective political project only within a united federation of European states, where the various identities would find respect and a common home. In other words, a unified Italy needed the United States of Europe in order to remain free.

In conclusion, it is notable how the experience of exile, common in a period of political persecution, contributed in distinct ways to the Europeanisation of intellectual elites in 19th-century Italy. During the Risorgimento – the name given to the long process of transition that transformed Italy from a cluster of principalities into a nation-state – intellectual exchanges and personal encounters helped to build a sense of Europeanness among a diverse group of European intellectuals and patriots.

Over the past century and a half, political visions of the European future have been deeply shaped by the networks of emissaries, exiles and intellectuals participating in national movements across Europe. This was important, because feeling European was not a straightforward matter for patriots caught in bitter and often violent struggles for unity and independence. It was precisely the failure of those struggles in the first instance that fed the exile networks, promoting the trans-European exchange of ideas and experiences that would generate innovative understandings of European unity.

The experience of exile also shaped reflections on the relationships between Europe and its many easts: the east that Konarski evangelised in Ukraine and Poland with Mazzinian revolutionary ideas and the secret cells of Young Europe; the east that Belgiojoso experienced in her journey through the Ottoman Empire, which blurred the boundaries between Europe and the East by embracing their plurality and arguing for the inclusion of Turkey; the east that Cattaneo imagined in his small study in Switzerland, defining the European experience of the self-government of the city against the foil of urban realities in China, India and Japan.

The leaders of the Italian national movement did not discern a contradiction between their patriotic effort for political emancipation and the commitment to a united and republican Europe. Just as they expected a Neapolitan and a Piedmontese to become Italian by loving their larger community without forsaking their native country, so the peoples of Europe would learn to love the larger European homeland. This reorientation of sentiment would not entail forgetting their national, regional or municipal affiliations. On the contrary: European patriots would come to understand and love them even more.

It might be not clear why the idea of Europe has often needed something eastern to think with to be defined, but what is clear is that Europe is still doing this, and the emergence of a European political unity is still constantly measured with debates on inclusion/exclusion of Turkey or, more recently, Ukraine.