Much-anticipated final verdicts from the EU’s highest court this week involving the abortive bid to establish a Super League are expected to shed light on the future of European football as well as the ‘constitutional’ position of sports in the EU Treaties.

In late 1995, the Luxembourg-based European Court of Justice (ECJ) delivered its famous Bosman judgment which allowed players to move to a new club at the end of their contracts without a transfer fee.

That judgment paved the way for players to enjoy the same freedom of movement rights as employees in other sectors with the effect of increasing footballer agents’ negotiating powers during contract talks.

More than twenty years later, with final judgment on the breakaway European Super League project established in defiance of Europe’s football governing body UEFA due early tomorrow morning, a December decision of the Luxembourg-based EU top Court has the potential once again to transform the football landscape.

These final and unappealable rulings of the 15-judge Highest chamber were scheduled on the very last day of the 2023 Court calendar.

The outcome will be presented together with two connected rulings on athletes sanctioned by the International Skating Union for taking part in external events and on the compatibility with the EU law of UEFA home-grown rules setting a quota of locally trained players.

Whatever the practical outcome of tomorrow’s verdict, it will set a milestone in the relationship between EU competition law and sports governance in Europe whose repercussions will reach beyond football.

What is at stake?

It began in late April 2021 when twelve of the world’s largest and wealthiest football clubs revealed plans to start a new midweek international competition, called the European Super League.

In theory, the breakaway tournament would have competed with the existing Champions League organised by Europe’s football governing body UEFA headquartered in Nyon, Switzerland, but Super League clubs wanted to keep playing in UEFA-organised national competitions.

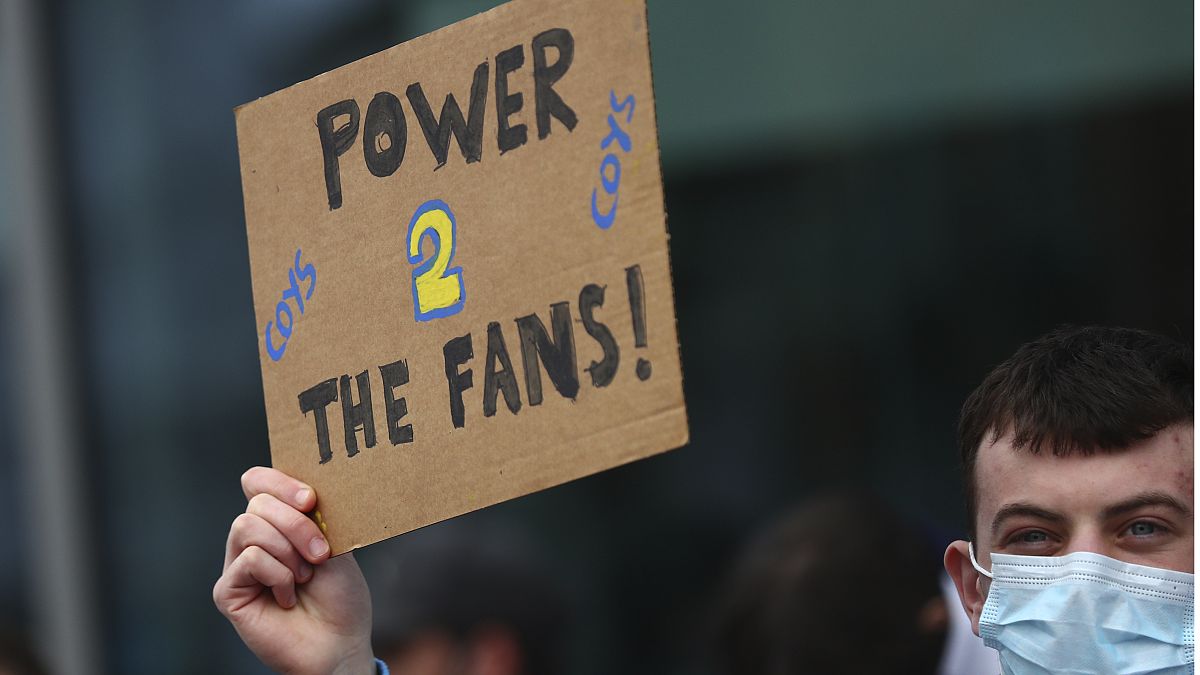

UEFA threatened to sanction or even ban rebel clubs from all other national competitions, and this threat, together with a global uproar caused by the announcement itself, ultimately led ten of the initial 12 Super League founders to withdraw from the project.

A Madrid Court called into play the European Court of Justice, asking it to rule on whether UEFA’s threats constituted abusive behaviour under EU competition rules which prevent dominant operators from abusing their powers.

At issue is the extent to which sports bodies such as UEFA may sanction their members seeking to establish other tournaments, and whether they may demand prior approval to set up new contests.

For representatives of the Super League, UEFA acted abusively in protecting its commercial monopoly; for UEFA, preauthorisation rules are essential to regulate international competitions and to assist it in fulfilling its mandate and preserving the integrity of European football.

The European Sports Model

The Super League case offers EU judges a unique chance to elaborate on the extent to which European sports bodies more broadly are exempt from the usual competition rules affecting businesses.

This issue hinges on the interpretation of Article 165 of the Treaty on Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) which refers to the commitment of the bloc to “developing the European dimension in sport, by providing fairness and openness in competitions and cooperation between bodies responsible for sports”.

This article gives “constitutional recognition” to sport highlighting characteristics such as systems of promotion and relegation as essential to a “European Sports Model”, according to the Advocate General Athanasios Rantos, who in December 2022 delivered the ECJ judges a non-binding opinion on the case.

If the judges reaffirm Rantos’ opinion, sports special constitutional place in EU law will be entrenched, EU sports lawyers and experts contacted by Euronews agreed.

According to another sports law expert, the judgment may also clarify the role and limitations in powers of sports governing bodies and of UEFA in particular – since the body is currently the football regulator, sanctions enforcer, and commercial entity negotiating TV rights for all the main football competitions in Europe.

Outcome one: monopoly wins

EU judges could consider UEFA to be a monopoly operator but consider it exempt from EU competition law as a guarantor of the football pyramid structure that ensures respect for the European Sports model, following Rantos’ interpretation of the special ‘constitutional’ status of sport.

European Super League advocates confirmed to Euronews that this scenario does not preclude the possibility of rival contests such as the European Super League’s but would make them unattractive as clubs joining a tournament outside the UEFA system would have to abandon their national federations and all other continental competitions managed by UEFA.

Such affirmation of a European Sports Model might also impact on those sports where closed competitions managed by private operators are the norm – such as Europe’s main basketball competition Euroleague, and two of Europe’s marquee sports events: cycling’s Tour de France and rugby’s Six Nations.

While the EU Court could rule in favour of a sports governing body maintaining both regulatory and organisational roles, it might not approve of UEFA also managing commercial aspects of the game.

The judges might also require UEFA to split its regulatory and commercial roles following the Formula One model where FIA takes care of organisational aspects such as safety regulations while private company Liberty Media operates races – this would be a sort of consolation prize for the European but is strongly opposed by UEFA, according to one lawyer contacted by Euronews.

Outcome two: game’s off for UEFA

The Court could rule counter to Rantos’ opinion, finding every entity has a license to compete and the right to participate in the sports market as long as it complies with certain criteria such as openness, solidarity, a commitment to grassroots and protection of players’ health.

This would give a greenlight to the European Super League project as well as future attempts to set up rival alternate sports competitions alongside traditional ones.

Denting UEFA’s actual monopoly on European football would remain challenging even if this scenario were confirmed, however, at least in the short term.

The Swiss-based football governing body has taken several measures in response to the Super League initiative since the announcement of the breakaway competition, particularly filling out the calendar of football fixtures.

Three years ago, UEFA introduced a third continental competition, the Conference League, and will next year launch a new model for the Champions League that will involve 36 instead of 32 participating teams generating roughly 50% more games.

This tactic would make it difficult for the Super League or other actors to negotiate with UEFA a share of the European football calendar unless clubs opt for the undesirable option of leaving the system.

In addition, UEFA currently enjoys exclusivity with international broadcasters on football competitions up to 2027 and even access to the biggest novelty in football, the FIFA World Cup for clubs, set to start in 2025, would be guaranteed through participation in UEFA competitions.