Several EU countries, such as Germany and France, already have space laws, but Brussels will present the first European Space Law in the coming months.

More and more satellites are being sent to space. Most of them move in what is known as low Earth orbit, about 1,000 kilometres from Earth.

One of the reasons for this increase is the growth in the uses of satellites, the more traditional ones such as meteorological or military, can now also be used to provide internet to remote places.

“The space race is growing and growing,” Gisela Süss of the European Space Agency (ESA) told Euronews.

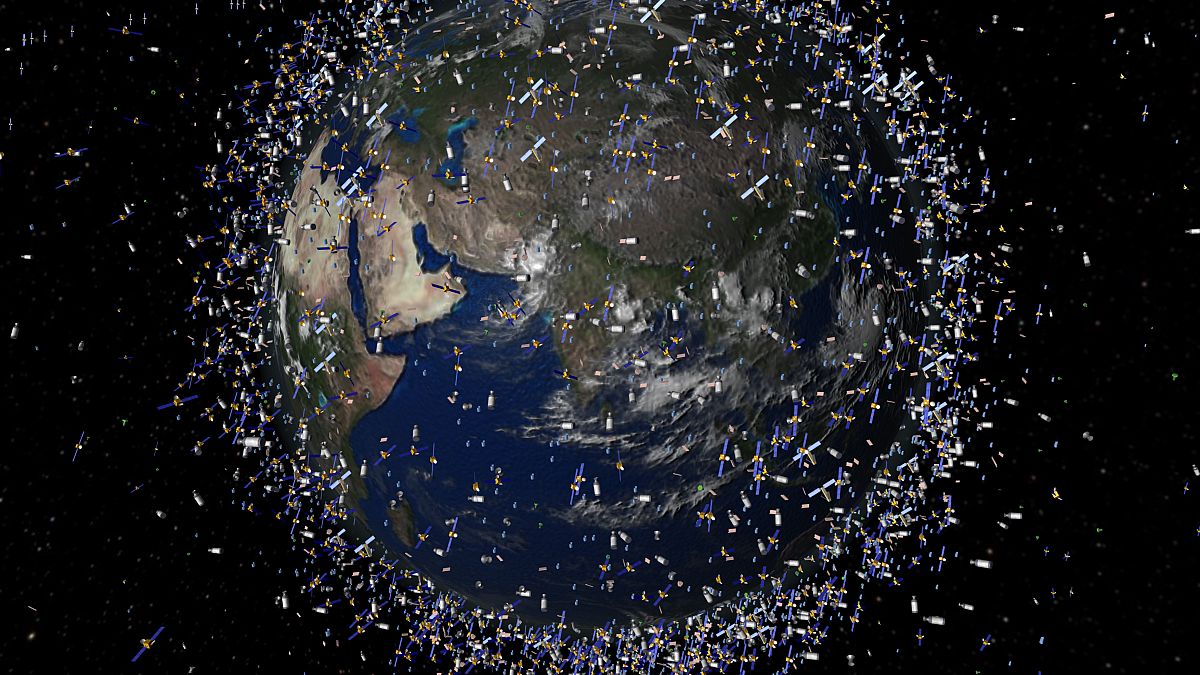

According to ESA data, there are some 12,500 satellites in Earth orbit. “Now, for example, we have constellations being launched into space from the United States, and it is increasingly becoming a business as well,” she said at the European Space Forum, held on 24-25 June in Brussels.

This has made it increasingly ‘interesting’ for private companies to send satellites into space, says Süss. She refers, for example, to projects such as SpaceX’s Starlink or Amazon’s Kuiper. Starlink currently has around 6,000 devices in orbit in various constellations, while Kuiper expects to add around 2,300 when the project is deployed.

More and more junk in orbit

The problem comes when the machines stop working, break down or collide with an object. In the past, satellites were unprotected against this type of incident, partly because it was difficult to modify their route, but now companies are seeking to minimise risks.

“All our satellites will have active propulsion systems, which means we will be able to manoeuvre them to avoid any collisions,” explains Jordi Casanova, from Amazon’s Kuiper Project.

In addition, the satellites will have “a specific type of shield so that, in the event of a small collision, the satellite elements will be protected”.

This is one of the measures to alleviate a problem that the European Space Agency believes threatens our future in space. Right now, there are some 2,700 devices in orbit that no longer work.

Added to this is space debris, made up of parts of old satellites or other materials created by humans and launched into space. ESA monitors some 35,000 pieces of debris, although it is estimated that there are millions of fragments measuring less than ten centimetres. These pieces orbit at high speed and can collide with and damage other devices.

To prevent their proliferation, the agency has launched its Zero Waste Charter. “The aim of this charter is to move towards zero by 2030,” says Süss, although the plan is “non-binding”. ESA also has measures in place to de-orbit satellites that no longer work, such as a robot that captures them.

Towards a new European Space Law

Several MEPs and experts have so far defined space as “the Wild West”. But years ago, the European Commission set out to regulate what happens beyond the Earth.

The need was born to create space legislation in what the European Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton called a “true single market”.

Several EU countries, such as Germany and France, already have space laws, but Brussels will present the first European Space Law in the coming months.

The proposed law was scheduled to be presented this spring, but its presentation has been delayed.

According to the European Commission, the proposal will take into account three pillars, including the security of satellite navigation, the protection of EU infrastructures against cyber-attacks and the development of the European space sector as a “major enabler of services”.