But gradually, and rather entertainingly, Limburg is upping its game.

The experimental art project Labiomista, in Genk, is a case in point. A tour of the project – erected on the site of a disused colliery, which later hosted a zoo – starts reassuringly enough at a three-storey, century-old Mosan Renaissance-style mansion that used to house the coal mine’s director.

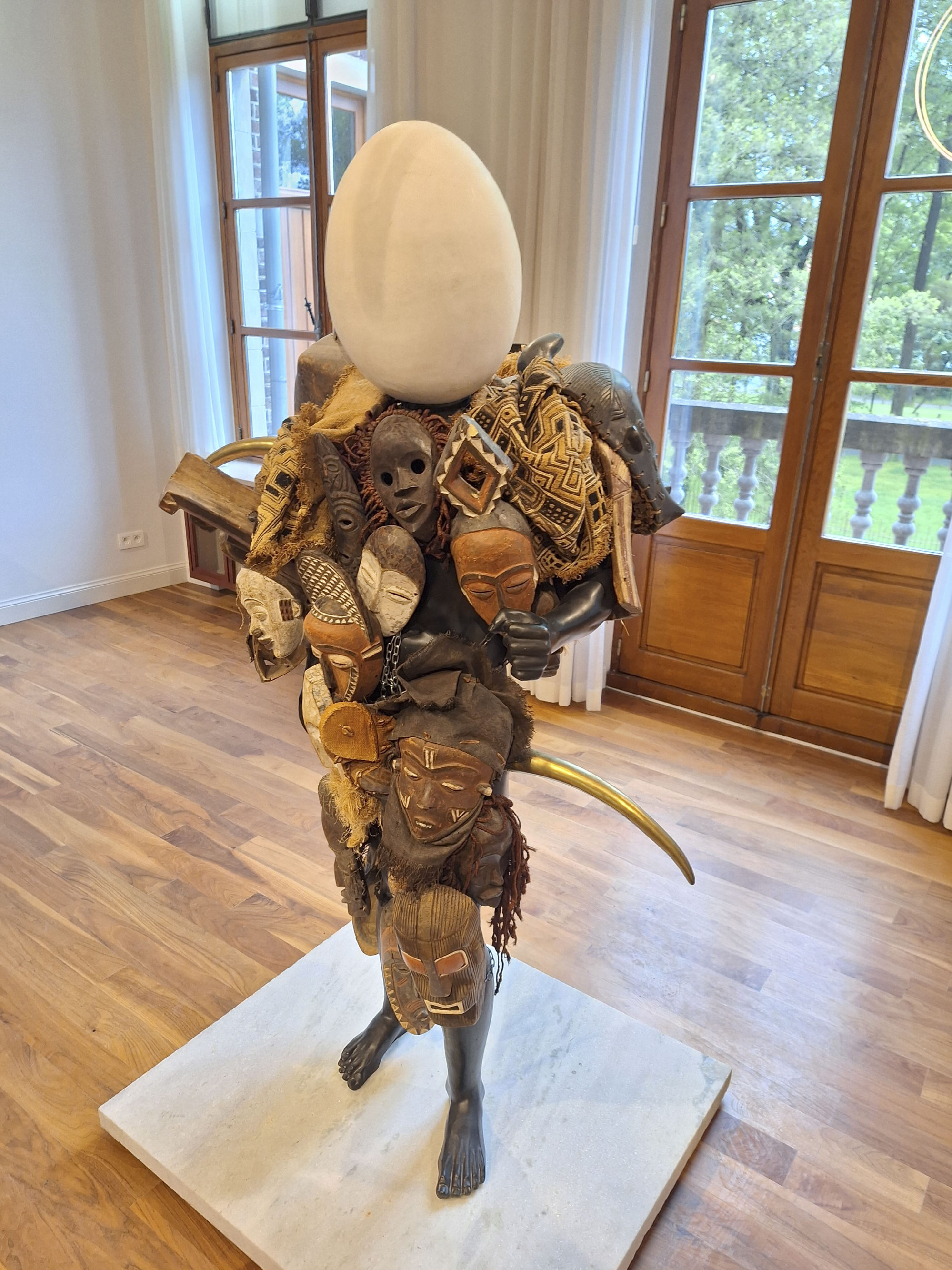

Step inside and a meteor shower of surprises starts in earnest in the form of sculptures and installations by pastry chef turned avant-garde artist Koen Vanmechelen, who specialises in bio-cultural diversity. Think a cluster of African masks surmounted by an egg, and a chicken clutching a dwarf suspended from the ceiling.

Beyond the mansion, Labiomista extends into a 24-hectare park dotted with similarly mind-boggling installations – the naked male with a horn growing out of his head and holding an owl proves especially popular with visiting school groups – interspersed with cages containing (real) camels, zebras and other animals, reminders of the site’s previous incarnation.

“We invested about €20 million [US$21.4 million] in the project, and I must admit there was some opposition locally at first,” says Wim Dries, the mayor who championed Labiomista’s genesis.

“Labiomista opened in 2019 and it’s proved an eye-opener, for local people and international visitors. It’s inspirational and very thought-provoking – about society, diversity, our connection with nature – so it’s turned out to be an enormous asset.”

Older than Labiomista but just as much a surprise in the heart of western Europe is the Japanese Tuin, or Japanese Garden, that sits by the outer ring road of Hasselt, Limburg’s capital, and a cherry-stone’s throw from the Albert Canal, which runs as far northwest as Antwerp.

Just as Huis Ten Bosch, a facsimile Dutch town, was erected outside the Japanese city of Nagasaki with painstaking authenticity, so Japanese Tuin was built in this remote corner of Belgium as a “stroll garden” in 17th-century Edo style, under the guidance of landscape architect Takayuki Inoue, to celebrate a partnership with the city of Itami, in Japan’s Hyogo prefecture.

Its 2.5 hectares (6.2 acres) make it the biggest such garden in Europe, and it is also – by virtue of being so utterly foreign – one of Hasselt’s top attractions.

Bridal couples pose against the backdrop of the Korokan ceremonial house, boisterous children dare each other to race across the Dragon Gate Waterfall, the Peace Bell gets a regular donging and the souvenir stalls at the end – ringed by 250 cherry trees – stock genuine artefacts such as calligraphy scrolls and takoyaki snacks.

“Throughout the ages, the Japanese have tried to preserve the essence of nature as much as possible, and the garden in Hasselt symbolises this,” says director Carl De Coster, who spent seven years working in Japan.

“To start off with, an expert gardener from Itami would come every few years to give some pointers and workshops on the pruning of Japanese pine trees, for example, but now we are pretty much able to run things ourselves.

“It’s a real oasis, and not at all something you would expect to find in this part of the country.”

Like the rest of Belgium, Limburg revels in its food and drinks – yet while the old staples of fries, beer and chocolate are available in abundance, there are distinct signs that the region’s chefs are branching out.

Michelin inspectors have raised their thumbs over the pigeon ravioli at The Thrill, in Genk, and chef Gary Kirchens’ fillet of lamb with parsley and nettle crust at Aurum, in Ordingen.

A recent arrival on the restaurant scene, Het Cordaat, which anchors a brand-new campus for start-ups, scale-ups and corporations on the edge of Hasselt, is part of the extensive culinary fiefdom of the 2024 Gault & Millau entrepreneur of the year, Dimitri Beckers.

With soaring ceilings and plate-glass windows, abundant greenery, and marble-topped tables, it serves items such as smoked eel and slow-cooked rabbit roll, as well as an entire menu page devoted to variations on the theme of gin and tonic.

“Nowhere else in the world offers the same amount of diversity and quality of food over such a small surface area [as Limburg],” says Femke Vandevelde, author of Belgium for Foodies.

“Plates of green, wild herbs, flowers and seeds that are not camouflaged by sauces, butter or added fats are things that make me happy. The soil here bursts with quality products like ground chicory, hop shoots, asparagus, and I like to be able to taste them in all their purity.”

A subtle, old-school hospitality is prevalent in Belgium’s less travelled regions. It is rare to come across someone in Limburg who does not have some command of English, halting or otherwise, and an eagerness to help.

That might entail scampering down a supermarket aisle in search of a particular brand of the thin gingerbread biscuit called speculaas, deciphering a bus timetable or wrestling with an unstaffed petrol pump that does not like foreign credit cards.

The pace of life is relaxed and hospitable too.

Town councils hire out bicycles at a mere €0.45 an hour; pavements, square and parks – even Labiomista and the Japanese Garden – may be busy at times but never frantic; grown men (and women) browse Tintin, Asterix and a host of other favourite titles for hours in comic stores; car-rental managers dispense free lollipops; and it is no surprise to turn a corner and find a bowler-hatted gent spinning out tunes on his antique barrel organ.