It’s one of the age-old conundrums for U.S. men’s national team players: Is it better to start games in MLS, or to be with a club in Europe, even with little to no playing time?

The question reflects the constant balancing act a player must contend with throughout his career, one that elicits a steady stream of additional questions too. What stage is the player at in his career: young upstart or grizzled veteran? What’s his contract situation? How important is he to the national team? How important is the national team to him? How does he find the right environment, the right playing style, the right coach and the right club?

If an American player is stuck, the decision often ends up being: Does he move to another overseas club or come home to MLS? This question is especially pertinent given the situations facing several U.S. players.

Gio Reyna endured a difficult spell on loan at Nottingham Forest, one that saw him log just 235 minutes. He is set to return to Borussia Dortmund with a giant question mark hanging over his future. Goalkeeper Matt Turner struggled for playing time at the same club. Ricardo Pepi is in a slightly better situation, but he’s clearly ready to be more than just a late-game super-sub for PSV Eindhoven, even after helping them win a league title. Similar conundrums face other players in the USMNT pool.

Often there are no easy answers, but among the players and coaches ESPN talked to for this story, there seems to be a consensus: getting on the field anywhere is better than not playing. A player’s technical development, mental toughness and confidence can’t improve from the bench, they say.

A look at the stats, however, paints a different — and perhaps surprising — picture where playing time is better off viewed as an indicator of national team strength, and not a determinant. Depending on the player’s position, club playing time might not matter as much as one might think.

So, with Copa América starting soon after two warm-up games against Colombia (Saturday) and Brazil (June 12), let’s dig into answering this question: Is it OK for the U.S. team if Americans are not playing regularly in Europe, or should those players go where they can get minutes, even if it’s stateside in MLS?

USMNT players are ‘not trained to sit on the bench’

DeAndre Yedlin‘s career has taken him from MLS to the Premier League to Turkey and back again. He’s now at FC Cincinnati and for him, the status of a league is secondary to whether it offers playing time.

“It’s obviously great to get experience, especially if you’re a young player, to be able to train with some of the top teams,” Yedlin said. “But at the end of the day, we’re not trained to sit on the bench. We’re trained to play. So, personally for me, I think that anytime you can play it’s better than not playing.”

American Jesse Marsch is looking at the issue from a new perspective. He is now an international manager with Canada, after previously working as a club coach where he managed in the Premier League, the German Bundesliga and MLS. For him, there is a middle ground for which players should strive.

“As a national team coach, I always want players playing, but I also want people challenging themselves,” he told ESPN. “And sometimes that means you’re going to fail. Sometimes that means it’s going to be hard. But I think in the end that will teach you more than just the ability to be on the pitch.”

For former U.S. international goalkeeper Brad Friedel, the situation is more nuanced. There will always be an impulse for players to push themselves to the limit. There are increased financial benefits to be accrued when a player heads overseas, as well as the chance for national team success. But those benefits have their limits.

“If you’re good enough to play in Europe, Europe’s far better,” he said. “But if you’re sitting on the bench, you’re wasting your career away. MLS is behind [Europe], but if you’re playing in MLS, you will get better, just at a slower rate. You’ll get better quicker than if you’re sitting on the bench and just training in Europe. But if you’re starting in Europe, especially in one of the top leagues, you’ll get better far quicker than if you’re in MLS.”

So how long should a player give it a go in Europe? How long is too long to be sitting on the bench before returning to the U.S. in search of playing time?

Friedel believes that two years of riding the bench is the maximum before it becomes an imperative to leave. That comes close to describing what he endured when he was at Liverpool early in his career. The club had signed Dutch international Sander Westerveld prior to the 1990-2000 season for £4 million, then a record fee for a goalkeeper. Friedel had been given his chances prior to that, but after making just four appearances that season, it was made clear to him that he would be the No. 2.

“I didn’t want to leave [Liverpool] but I needed to go play,” he said. “I fought it out as long as I could, until I saw that point where I was going to actually be an incumbent number two. That was not me.”

For Friedel, returning to MLS — he had spent two seasons with the Columbus Crew — wasn’t really an option. The league was still in its infancy at that point. It’s a more viable option now, he says. But in this instance, he latched on with another English side, Blackburn Rovers, who had a manager (Graeme Souness) whom Friedel had worked with before at Galatasaray.

The move ultimately panned out for Friedel — he went on to become a Premier League staple, making over 500 appearances for the likes of Aston Villa and Tottenham Hotspur. A move back to MLS, had it been an option, however, would have put Friedel’s career on a much different path. After a player moves to MLS from Europe, he is far less likely to ever return to the upper echelons of European soccer — another factor players must consider.

Less club playing time, worse USMNT performances?

Diving into the “Does club playing time matter for national team performance?” question can drive you bonkers.

Just watch: Does it matter? If you’re not playing for your club team, then you’ll be rusty for your national team. But does that mean that players are making themselves worse by playing for better teams where there’s more competition for playing time? Doesn’t the fact that these players got recruited by better teams simply mean that these players are… better?

But then… doesn’t the fact that these players aren’t playing — they aren’t chosen by the coaches who see them play every day in training — suggest that they’re actually not good enough to play for the team that recruited them? And they might actually be worse off because they’re both not as good as we thought and rusty? And the guy who never left for a bigger club is also not good enough to play for a bigger club, but is at least getting lots of game time for a smaller club and therefore in better condition to perform in whatever the upcoming international tournament is?

But… aren’t these teams constantly firing their coaches and don’t these coaches all have their own specific tactical preferences and don’t we know that lots of coaches sacrifice individual talent for talents that specifically match their systems?

I’ll stop it there, but it can go on and on and on.

The truth is that the best national teams in the world don’t really have to worry about this. If there’s an English or French or Brazilian winger who isn’t getting playing time for Real Madrid, then there’s going to be an English or French or Brazilian winger who is getting playing time for Arsenal. This is borne out in the numbers.

“Looking back at World Cup and European Championship final tournament squads since 2010, which includes 4,500 players, we can look at how many league minutes players had played the nine months prior to the tournament starting,” Aurel Namziu, senior data scientist with the consultancy Twenty First Group, told ESPN. “We tend to see that the average player played 1,764 minutes (about 20 league matches). Only 6% of players who got called up had played fewer than 500 league minutes.”

In other words, most players who aren’t playing at the club level simply don’t even get called up to the national team in the first place. That makes it tricky to actually measure whether there’s any crossover between club-and-country form. But the trend would at least suggest that managers certainly think so.

So, for the U.S. team at the Copa América, who’s coming in below the average mark? We’ll look at the outfield players from this past season and exclude all of the MLS players.

All of the defenders from the provisional Copa América roster have played at least 1,800 minutes. Among the midfielders: Tyler Adams (121 minutes for Bournemouth), Yunus Musah (1,478 minutes for AC Milan), Gio Reyna (515 combined minutes for Borussia Dortmund and Nottingham Forest) and Malik Tillman (1,639 minutes for PSV Eindhoven) all fall below the average participation and rate. And for the forwards: Brenden Aaronson (1,267 minutes for Union Berlin), Folarin Balogun (1,692 minutes for Monaco), Ricardo Pepi (484 minutes for PSV) and Timothy Weah (1,258 minutes for Juventus) all missed the mark.

There are three potential conclusions here: (1) it doesn’t matter if the players get on the field for their club, (2) these players are going to play worse in this summer’s Copa América than they have in the past or (3) this says something about the overall talent level of the USMNT pool but shouldn’t have much of an effect on how these same players play for the national team this summer when compared to how they played for the team in the past.

The most plausible seems to be the third option. Obviously, a lack of game time will affect some players more than others, but overall, it appears this just tells us that the U.S. team is filled with players who are good enough to earn minutes for teams in the Champions League and across Europe’s “Big Five” top leagues, but not many stars who can be relied upon week in and week out.

Twenty First Group has a player-rating model that looks at how many minutes a player plays, how good his team is and how much he contributes to defense and attack. So, it’s accounting for the quality of the teams the Americans are playing for but also how much they’re playing.

Per that system, the top 25 USMNT players comprise the 30th-best national team pool in the world. The U.S. is No. 1 in Concacaf and is the fifth best from all the teams in the Copa América field — behind Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Colombia.

Fifth-best team in the field is right around where the bookmakers see the Americans for Copa América, too. That’s not, necessarily, specifically because Reyna and Balogun haven’t played a ton of minutes this season, but rather because of what their lack of minutes says about their overall effectiveness once they step out onto a soccer field.

Are goalkeepers a special case?

Now, there is a position where playing time doesn’t seem to be as important. And luckily for the USMNT, it’s the role where the team is currently the weakest: goalkeeper.

Matt Turner played only 1,530 minutes for Nottingham Forest in the Premier League this past season before losing his starting job. Ethan Horvath didn’t play at all for Nottingham Forest this past season — before leaving midseason for Cardiff City in the Championship, where he played 1,440 minutes. Third stringer Sean Johnson, with 1,080 minutes for Toronto FC, has already closed in on both of them in playing time despite the current MLS season being only a couple of months old.

“Goalkeepers are an interesting case study and perhaps a position where this [playing-time] hypothesis is less true,” Namziu said. “In the data I looked at, 11% of all goalkeepers called up to final squads had played fewer than 500 league minutes. This was significantly higher than other positions, with attackers behind the second lowest at 6%. So, club minutes matter less for goalkeepers than any other position.”

This makes sense on a structural level. Every team in the “Big Five” leagues has multiple players at every position who get significant playing time, while most of them only have one goalkeeper. There aren’t many minutes to go around for goalkeepers.

At the same time, you’d think that goalkeeper would be the position most affected by rust.

Say you’re a midfielder who is getting only spot minutes for his club team. Once you get thrown out there for the USMNT, you might misplace a pass or two, not be as crisp in turning out of pressure, or whatever. But you at least have the opportunity to get enough touches to regain some of that form, while your mistakes just won’t be that important. For a goalkeeper, you’re only facing a couple of shots a game, so you’re not getting enough touches to get back into flow. And if you miss a ball or drop a cross because you’re rusty, it’s probably going to lead to a goal for the other team.

Still, there have been plenty of goalkeepers who performed well at an international tournament despite not playing much at the club level. In 2014, Argentina made it all the way to the final with a keeper, Sergio Romero, who barely had played for Monaco the season before. In 2018, Morocco and Nigeria‘s keepers both played well despite not featuring much at all at the club level.

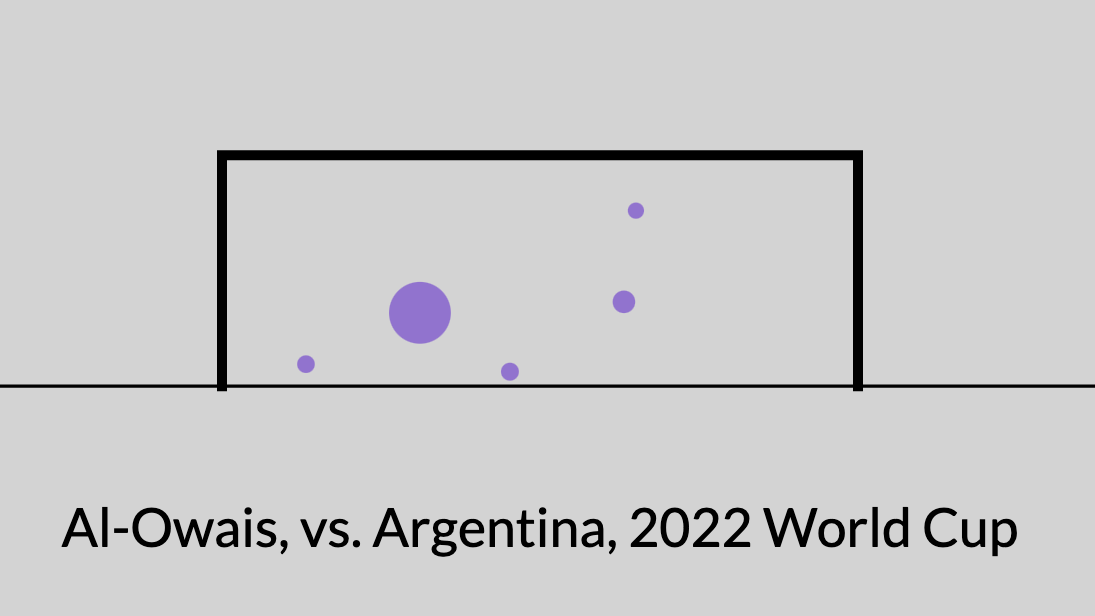

And in 2022, Saudi Arabia‘s Mohammed Al-Owais stood on his head in their shock defeat of Argentina. He made five saves and conceded one goal, a penalty, from attempts with a post-shot expected goal value of 2.52. The larger the circle, the higher the expected-goals value of the attempt, and while purple are shots, orange would signify a goal:

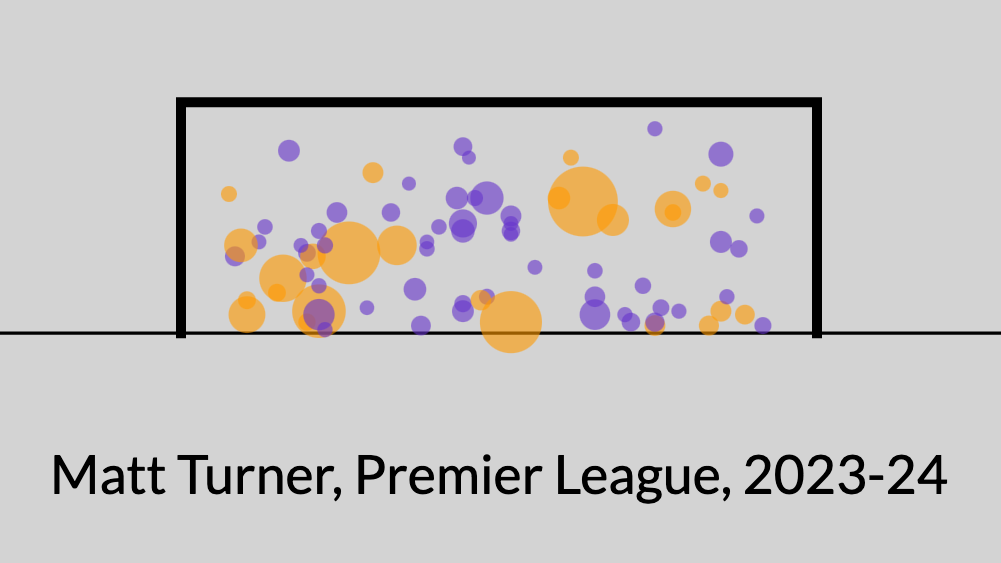

Turner himself was fine in 2022 too, despite playing a whopping zero league minutes before the World Cup in Qatar. He conceded four goals from 3.44 post-shot xG. That’s right about average and comes out to just a goal per game.

However, he has been way worse than that at Forest, conceding 28 goals from 22.55 expected:

If there’s a problem for the U.S., then, it would seem less that Turner hasn’t played a minute of professional soccer since February and more that he was playing so poorly that Forest decided they would be better off if they stopped playing him.

The other side of club decisions: Mentality matters

When a player makes a decision about where to play, it will not only affect short-term stats, such as the minutes they get or how many goals they score. It will also have long-term effects on intangible factors, such as the player’s mentality and confidence.

Friedel recalls how the expectations in Europe are greater, the consequences for a bad performance, or even a bad practice, more severe, especially with promotion/relegation involved. That requires not only an immense amount of discipline, but a mental toughness to deal with the constant pressure.

“When I was at Blackburn, if we had lost to Burnley, for instance — which thankfully we didn’t when I was there — there would be a whole host of fans sitting around our cars like wanting to knock us out. Really. You have to go out with your security and that’s at a small club. Now, I’m not saying that that’s good behavior. I’m not saying that that’s the way it should be. I’m just saying that’s the way it is.”

Yedlin speaks in similar terms when it comes to the mental aspect. When he first joined Tottenham in 2014, he was a U.S. international coming off a relatively successful World Cup. But when the playing time didn’t come right away, his confidence plummeted. It took an even bigger hit when he was left off game-day rosters. He admits now that he was “quite immature” in dealing with such setbacks.

“I could feel it as a player,” he said about his lack of confidence. “Things just don’t come off like they usually do.”

It was during a loan move to Sunderland — and later with Newcastle — that Yedlin began actively working on the mental aspects of his game. He read self-help books, practiced meditation and researched the spirituality around Buddhism. He noticed that his performances suffered when he stopped doing the mental work, so it became part of his daily routine. Was it an unorthodox approach? Maybe. But it worked for Yedlin.

“The game is the game, but I think it’s so much more mental than physical,” he said. “For me, it was just learning that aspect of it. Then it started to help me as far as life goes, being a good father and husband.”

Marsch certainly knows the pressure players are under in Europe — he faced two relegation battles at the helm of Leeds United, one (2021-22) successful in keeping the team in the Premier League, and one (2022-23) that saw Leeds go down after he was let go. The players who aren’t getting onto the field for their European clubs are missing out on that high-stakes intensity, no matter how good the training environment is.

“There’s things you can establish at training, but there’s not the same level [as a game],” Marsch said. “The biggest difference between MLS and Europe is the pressure of big games and the pressure of promotion and relegation and the pressure of achieving Europa League or Champions League or whatever. I mean, these wind up being monumental moments in clubs’ and players’ and coaches’ careers that can really determine so many different things. And there’s a million variables that go into it. But you have to be on the pitch as a player, understanding that each game in every moment matters so much.”

As far as Friedel is concerned, the higher demands in Europe can lead to player growth quickly in the first few months following a move abroad, even if it isn’t immediately accompanied by playing time. But a high level of adaptation is required.

“Some technical aspects can be sharpened,” he said about when a player makes the move to Europe. “Details tactically, a player can improve. But the biggest thing is mentality.”

A move by an American from Europe back to MLS can be viewed as admission that they are done trying to play soccer at the highest level and are looking for a less competitive team environment. But Yedlin notes that transfers aren’t always purely soccer-driven decisions, especially when a player returns from Europe.

There are plenty of instances where personal circumstances drive moves back to the U.S. domestic league. Colorado Rapids midfielder Djordje Mihailovic, for instance, alluded to precisely that scenario when he returned to MLS prior to the start of this season.

But ultimately, like so many other aspects of the sport, the decision to stay or go is an intensely personal one.

“Nobody’s trying to make a decision that going to diminish their career or anything like that,” Yedlin said. “Everybody tries, I believe, to make the decision that they feel is best for that point in time.”