Action has always sold comic books in the United States, with the crash-boom-bang of justice-seeking superheroes creating a kinetic visual language that spawned not just a billion-dollar-a-year market for paper and ink, but a seemingly endless stream of multi-billion dollar movie franchises. And yet, despite the massive success of the Fast and Furious series alongside more traditional Marvel-sourced comic book movies, there has been relatively little cross-pollination from the screen to the page when it comes to depicting tales of cars and racing.

Car culture is seriously under-represented in American comics, with only a scattered handful of independents tackling the topic directly. Even major titles like Archie, set in a semi-timeless space defined largely by ’50s soda pop shoppe mores, typically employed the hot rods and jalopies driven by the main characters as more background dressing than subject matter.

Cast a gaze overseas, however, and you’ll discover a long-standing love affair between gear oil and comic geeks. The marriage has cultivated a number of critically-adored and hugely impactful graphic novel gems. More so than others, there are three countries outside of America that have had an outsized influence shaping automotive narratives in comics, each thanks to unique cultural circumstances that favor particular comic book traditions over the superhero genre.

Franco-Belgian BDs

For most of their history, American comic books struggled to push past their roots as inexpensive entertainment aimed almost exclusively at children and teenagers. There was even a massive movement in that 1950s that Mainstream acceptance of the medium’s capability of telling adult stories stretches back only 25 years or so.

In France, comics have enjoyed a very different appraisal from the cultural elite. Although the youth market was of course accounted for, from the 1920s onward, these Bandes Dessineés, or “BDs”, moved quickly from the magazines and newspapers that gave them their start into collected and bound editions that tackled adult-oriented story lines. Alongside Belgium, which gave the world the ultra-popular Tintin and Smurfs series, France’s post-World War II entertainment industry assigned almost equal weight to series like Lucky Luke and Asterix as it did the New Wave of cinema that was also beginning to emerge from within its borders.

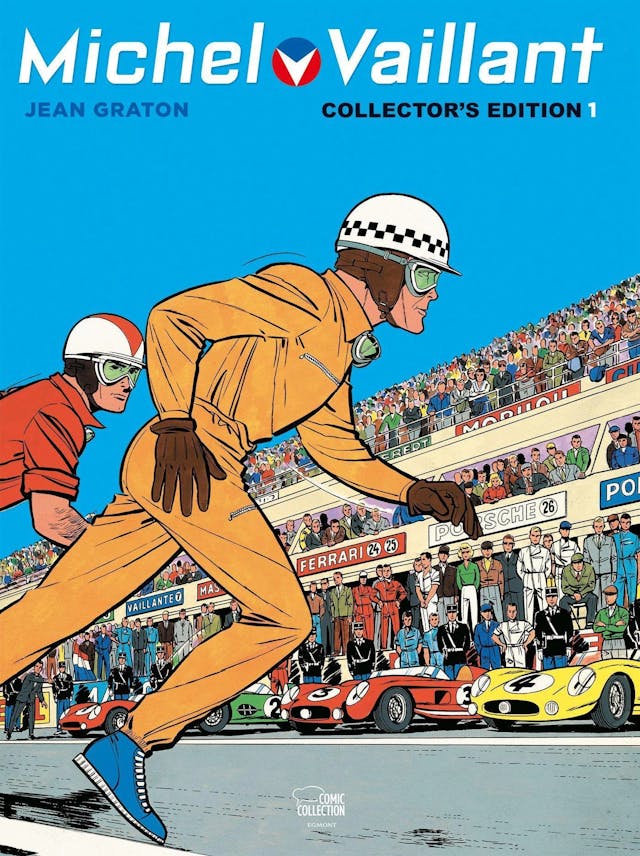

It was from this crucible that the world’s most successful racing comic book was born. In 1957, Belgium’s Le Lombard published a new series from French writer and artist Jean Graton titled Michel Vaillant—the name of a man considered (within the universe of the comic book) to be the best talent in motorsports. Le Lombard was responsible for the wide-ranging Tintin magazine where Vaillant made its debut, and Graton’s art style and prose-heavy narrative made it a natural companion to the work of Hergé (the pen-name of Tintin’s creator, Georges Prosper Remi).

It wasn’t long before Vaillant’s on-track exploits had graduated from magazine strips to hardbound volumes of their own, where French and Belgian fans devoured the adventures of driver Michel, his Vaillante (translation: Valiant) family racing team, and his American driving partner Steve Warson. The books tackled series as diverse as Formula 1, Le Mans, IndyCar, and world rally. The action was set on real-life tracks familiar to any fan of motorsports competition, with the cars and racing faithfully depicted. Popular drivers (including Gilles Villeneuve and Didier Pironi) even made cameo appearances in several volumes, further tying Michel Vaillant to the automotive icons of its era.

“There was no better, more entertaining way to learn about the racing world,” says Michel Crépault, veteran automotive journalist and BD expert. “Jean Graton visited each track to make sure what appeared on the page was as realistic as possible. Jacky Ickx was a recurring character in several volumes, and Alain Prost even said that reading the adventures of this not-so-fictional driver helped lead him to his own F1 career.”

While the drama might have occasionally been over the top—the initial book in the series, “The Great Challenge”, deals with a private, globe-spanning contest funded by a Midwestern newspaper to determine the world’s greatest driver—the template was set for more than 70 successful books as well as both live-action and animated television series. The original print run lasted until 2007, when the writing and art passed from Jean Graton’s hands into those of the studio he had originally founded and his son Philippe. A second series arrived in 2012.

The influence of Michel Vaillant reflected back onto the very motorsports it glorified. In 1997, the Courage team ran a “Vaillante” prototype car in the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Bearing the famous comic book livery and number 13, its team of French and Belgian pilots took home fourth place in their class with proud Graton father and son in the garage. In 2017, Rebellion Racing entered a “Vaillant Rebellion” tandem in the FIA World Endurance Championship, winning the LMP2 title. Art imitating life, imitating art.

Tofu, Speed Racing, And Wangan

Japan’s manga tradition is even older than France’s BD, dating back nearly 800 years but popularized in the form most closely resembling its modern iteration in the late 18th century. As with Bandes Dessineés, manga surged post-1945 and was universally embraced at nearly every level of Japanese society as a legitimate medium for storytelling, regardless of the audience’s age.

Although the term encompasses a vast cultural phenomena, manga is known for its black-and-white aesthetic, as the tight schedules of the weekly storylines that drive its frenetic pacing allow no time for a colorist to work their magic. Given the rapidity of its production, it’s not surprising that a successful modern manga series can span dozens of volumes, making it almost as much of a challenge for readers to keep up with the plot as it is for publishing houses to churn out each title.

In Japan, the genres spanned by manga include everything from children’s stories to science fiction, domestic drama, and erotica. With such a mainstream reach, it’s no surprise that manga has also long celebrated car culture, a subject almost as important to that country as it is in the United States.

Three automotive manga series in particular stand out, two of whose titles need almost no introduction. Almost every American is familiar with Speed Racer, based on a manga called Mach GoGoGo that first appeared in 1966 chronicling the titular driver’s global racing escapades (and a work that has lead to multiple adaptations in television and film). This was followed by the almost-as-popular Initial D, a drift-focused story of a Toyota AE86 Corolla-owning tofu delivery driver. Initial D spread across 48 original volumes as well as a vast array of cinematic, small screen, and even video game adaptations.

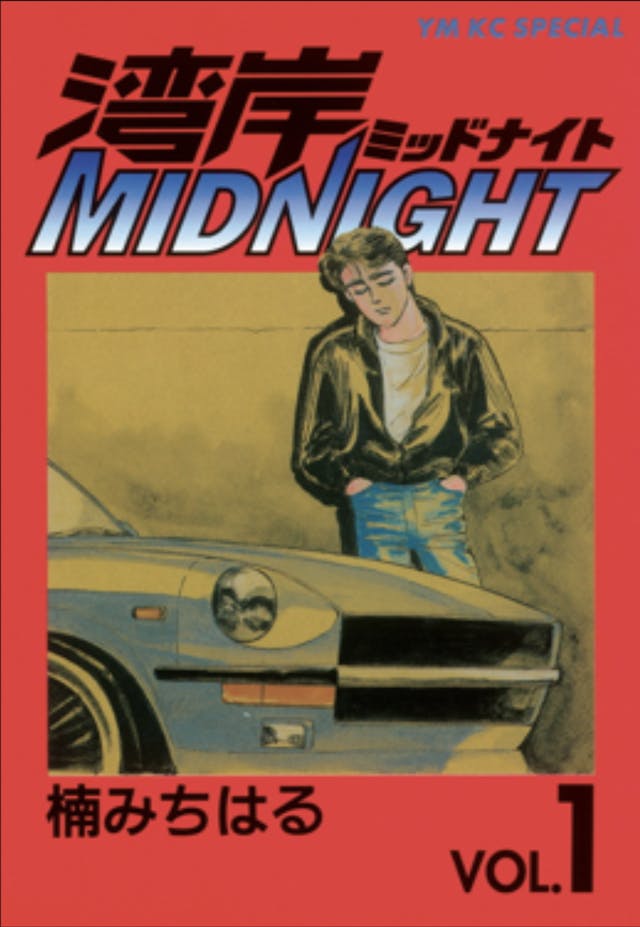

The third member of Japan’s car-centric manga triumvirate is lesser known outside of the island nation, but no less influential. Wangan Midnight was created and drawn by Michiharu Kusonoki, who had spent much of the ’80s as the writer and illustrator of Shakotan Boogie,—a chronicle of the Japanese lowrider scene. Beginning in 1990, Kusonoki turned his attention to the hardcore street racing that occurred along Tokyo’s Bayshore Route (otherwise known as Wangan), while also introducing a supernatural twist previously absent from Japanese automotive narratives.

The plot of Wangan Midnight centers not just around its characters, but rather the specter of the “Devil Z,” an S30-generation Datsun with a twin-turbo engine swap that has claimed the lives of several of its owners in mysterious racing accidents. The series begins with Akio Asakura pulling the Z out of a scrapyard—against the advice of everyone around him, who are convinced that the coupe is cursed. The Devil Z keeps its original plate (Asakura also shares the same name as its most recently deceased pilot) and is viewed as a ghost when it returns to Wangan action, where its demonic power provides it with enough speed to outrun the various Porsche 911, Nissan GT-R, and Ferrari Testarossa rivals it encounters.

Although overshadowed internationally by the exportation of drift culture that pushed Initial D to global recognition, Wangan Midnight ran to a similar length, with four additional manga series following its first run. Not only that, a baker’s dozen of films based on the Devil Z’s exploits were released from the early ’90s until well into the 2000s, with a television show and 15 distinct Wangan Midnight video games also appearing as recently as 2021.

The Future Of Car Comics

Unlike BD, manga has managed to make significant inroads among American comic book readers, particularly the fast-growing young adult demographic. It’s no surprise, then, that automakers have increasingly turned to manga and its on-screen counterpart, anime, as marketing materials.

Nissan created a manga history of the GT-R model that launched at the same time as the R35 generation reached U.S. dealerships. More recently, Toyota produced a Corolla history in the same format. Acura has also gotten in on the act with an anime series dedicated to its Type S performance line.

The limited translations available for BD, outside of heavy-hitters like Tintin and Smurfs, make that genre less likely to crack into the global mainstream with another racing-focused title. Manga is another story, and it continues to break sales records in the United States, thanks in large part to its ability to hook readers young and then carry them into adulthood with its extended storylines and accessible pricing.

To feed America’s obvious appetite for automotive content, something like a manga featuring the Toretto fam’s adventures feels poised to be the perfect delivery method for inspiring the next generation of gearhead artists to draw stick shifts and tire smoke instead of capes and tights. It’s high time for an American spin on the comic book style that originally celebrated Wangan midnights and Tokyo drifts to start living its life a quarter-mile at a time.