Because women have fewer options and their work gets devalued, job segregation accounts for half the gender pay gap in Europe.

Women still face disadvantage on the labour market, earning close to 13 per cent less than men on average across the European Union in 2022. While most policies—pay transparency, awareness-raising or anti-discrimination legislation—address pay gaps between men and women in the same job, much less attention is generally given to the separation of men and women into different jobs.

A growing body of literature focusing on what happens within workplaces shows that women work in lower-paying workplaces than men, partly because they are more often constrained by family or other concerns when looking for a job. Moreover, even within those jobs they still tend to earn somewhat less than men. Such segregation has a sizeable effect on gender pay gaps.

Overlooked issue

Job segregation, where men and women work in distinct industries, occupations and workplaces, not only perpetuates wage gaps but also in itself influences job evaluation and work conditions. Work that is predominantly done by women tends to be evaluated as worth less and of less impact, which in turn affect wages and conditions. Such devaluation has been the topic of several studies across countries, as one explanation for why wages tend to decline in those jobs that are more feminised.

A recent study by the European Trade Union Institute looks at the separation of men and women into different jobs across the EU from the early 2000s to the 2020s. It sheds light on this overlooked issue, when considering gender equality, of where men and women work.

In 2018 across the EU about half of the pay gap between men and women occurred within workplaces and types of jobs, so about half was due to men and women doing different jobs. Sometimes this is interpreted as implying inaction—it is taken-for-granted ‘difference’, not ‘inequality’—but we must ask the underlying question: why do women work in lower-paying positions and workplaces? An important reason is that women generally are more constrained and have fewer options, but also that jobs more women do offer worse conditions.

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

Negative association

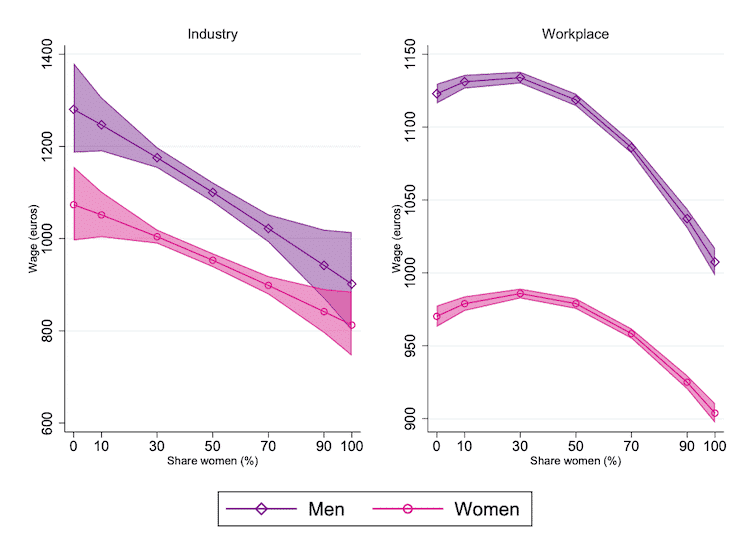

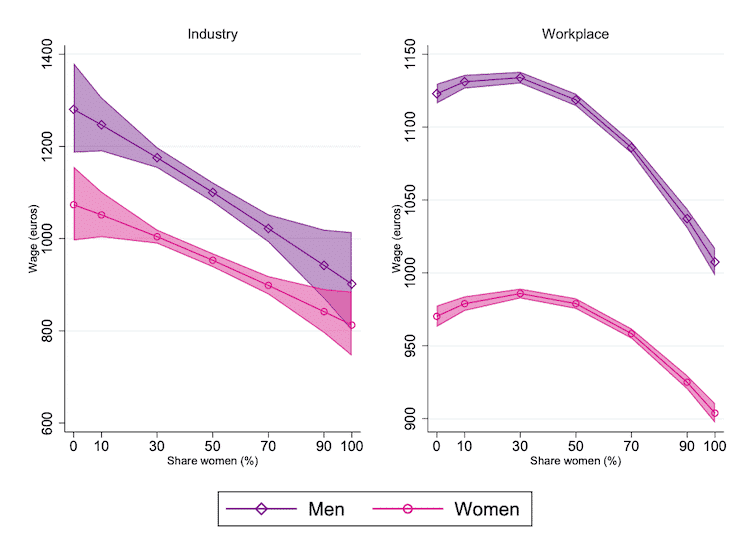

Segregation does not only occur between sectors but is also sizeable between workplaces (Figure 1). Generally, there is a negative association, in both cases, between the share of women among employees and the average wage. It may be that women are more likely to work in lower-paying places, having other considerations beyond the wage in mind, such as location of the firm or work-life balance; or it may be that the sectors or workplaces in which more women work are able to pay less for some reason.

Figure 1: relation between the share of women in an industry (left) or workplace (right) and the average wage for men and women in that industry or workplace

Analysing trends over time and job quality across EU member states reveals a consistent pattern: a ten-percentage-points increase in the share of women within a job is associated with worsening conditions. This includes a 10 per cent increase in low-wage earners, a 15 per cent rise in involuntary part-time positions, a 5 per cent increase in temporary contracts and a 5 per cent decrease in supervisory roles. These negative changes affect both men and women, emphasising that the issue extends beyond gendered pay gaps to alterations in overall job dynamics.

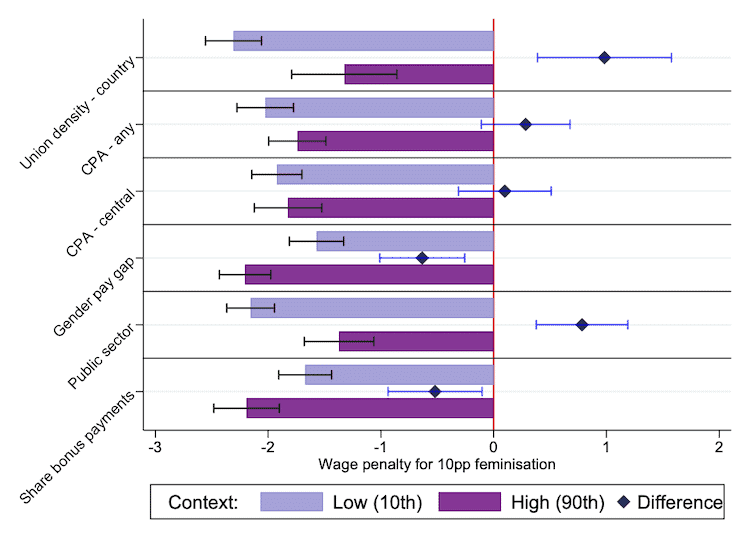

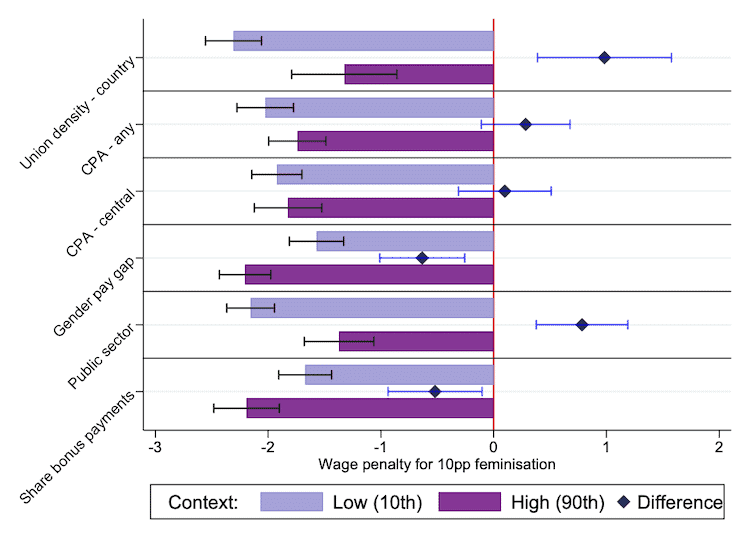

While the feminisation of a job is generally associated with deteriorating conditions, the extent of this impact varies across countries and sectors (Figure 2). Greater bargaining power for workers and stronger oversight of pay setting—as with stronger union density, higher collective-agreement coverage, and a substantial public sector—temper these negative effects. Conversely, in countries with wider pay gaps and less control over bonuses, the impact of feminisation is more pronounced, highlighting the role of employers’ discretion in wage-setting and its contribution to harmful stereotypes affecting labour-market conditions.

Figure 2: how the wage penalty for women associated with a ten-percentage-points feminisation of work is affected by contextual variables, comparing low (tenth percentile) and high (90th percentile) scores for each such variable

Way forward

This also points to the way forward. First, of course, provide women with all opportunities to compete on a level playing field, meaning also support with caring obligations and childcare.

Secondly, do not believe that because pay gaps reflect differences in where men and women work that this is in some way less problematic than the gaps in pay for similar work: why would people choose lower pay if all else is equally? Here the introduction of a hypothetical comparator in the 2023 pay transparency directive is an important step forward, as a recognition that men and women too often work on different jobs. Devaluation however affects men and women in more feminised jobs and may therefore not be addressed purely by focusing on gender pay gaps.

Thirdly, provide support to workers to ensure better conditions for all.